By Olivier Bault.

Poland – This time the French mainstream media were much more vocal than during the French president’s October meeting with the Hungarian premier in Paris. Emmanuel Macron’s trip to Warsaw on February 3–4 was described as a turning point in relations between France and Poland. Forgotten are the days when Macron said, while on a visit to Sofia in 2017, that the Poles deserved a better government than the one they had or, in Bratislava the following year, that Poland and Hungary were led by “crazy minds” “lying to their peoples”.

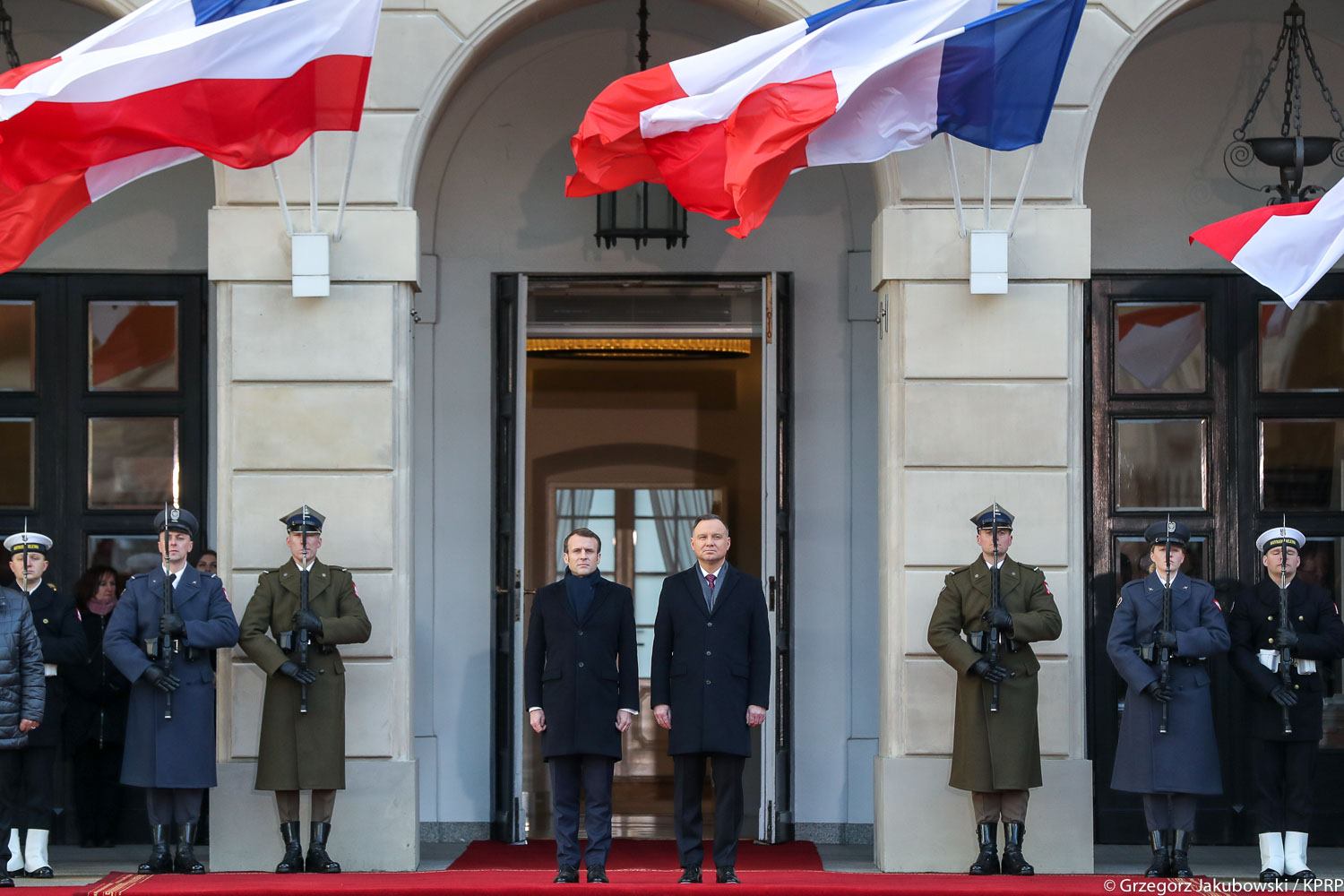

Accompanied by several high-ranking ministers, and in particular by foreign affairs minister Jean-Yves Le Drian and defence minister Florence Parly, the French president was in Warsaw to discuss European defence, energy and the climate with his Polish counterpart Andrzej Duda and Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki. Discussions were also held at ministerial level and between Emmanuel Macron and the speakers of both houses of parliament (including the speaker of the Senate, who belongs to the Civic Platform liberal opposition party). There were also meetings between company managers from France and Poland, for example on the question of the potential market for French nuclear technology at a time when Poland has to gradually phase out coal, which still accounts for some 80% of its energy production. Macron took care to reassure his Polish partners after his remarks on the brain death of NATO and the need to renew the dialogue with Russia: European defence is intended to be the European pillar of NATO and not to replace the alliance with the United States, and France is neither pro-Russian nor anti-Russian, but pro-European, he said.

Before Macron’s arrival, some Polish media had raised the possibility of an agreement to send Polish soldiers to the Sahel region, where France is asking for European involvement, suggesting that in exchange France would give up its demands for the redistribution of asylum seekers at European level. However, this was not mentioned during press conferences and press releases after the meetings held in Warsaw.

It is nonetheless clear that the departure of the United Kingdom is going to bring about significant changes in the European Union. Although France intends to continue its military cooperation with the British, it is now the only country in the EU with a capacity to deploy forces on other continents. In this context, Poland, which is one of the few European countries to fulfil the NATO objective of spending 2 per cent of GDP on defence, could become a cornerstone of a future European defence system. This issue headed the topics addressed in the Franco-Polish Declaration on cooperation in European matters signed in Warsaw on February 3.

As French and Polish media pointed out, the French president seems to have realised that Franco-German cooperation alone is not enough to push forward his projects for reform of a European Union with 27 member states after Brexit. In addition to the reluctance of Germany to support Macron’s euro-federalist proposals, other countries must be reckoned with, including Poland and its Visegrád Group partners, who share a much more Gaullist vision of European integration.

One should bear this context in mind when considering Macron’s statements to the press, made in Warsaw on Monday, and also during his speech on the subject of “Poland and France in Europe” at the Jagiellonian University in Krakow. Interviewed on Monday on the Polish reforms of the judiciary, which are at the centre of four years of conflict between the PiS governments and Brussels, the French president said that France should not lecture Poland and that this was not a matter of relevance to bilateral relations between member states of the EU, but that, at the same time, Paris supports the action of the European Commission with respect to Poland. On the next day in Krakow, Emmanuel Macron referred extensively to the principles and fundamental values of Europe, which he considers to be defended by the European Commission. “Do not believe those who tell you: ‘Europe will give me money for climate transition with one hand, but will allow me to make my own political choices with the other’”, the French president warned once again, returning to his traditional rhetoric regarding the link between European funds and the respect of “European values”.

At a time when there is an ongoing conflict in Poland between parliamentary democracy and judicial activism, with the European Commission openly siding with the latter, the words of the French president clearly indicate that opposite conclusions have been drawn from Brexit on the banks of the Seine and the Vistula: the French hope that the European Union will now evolve towards a more federal Europe without having to go through new treaties, thanks mainly to the action of the European Commission and the very loose interpretation of existing treaties by the Court of Justice of the EU, while the Poles do not accept that Brussels should take over competences in areas which are not explicitly provided for in the Treaty of Lisbon.

Hence, although France and Poland appear to have got on very well together in Paris and Warsaw, they are likely to be on opposite sides of a violent confrontation in Brussels. In this sense, and even though according to opinion polls Polish people (and also Hungarians) remain much more pro-EU than the French, Brexit Party leader Nigel Farage may very well have been right when he forecast in his last speech in the European Parliament that the European Union will no longer exist in 10 years’ time.