By Nicolas de Lamberterie

“Lovas is dead”

“Lovas is dead.” Those were the three terrible words to which I awakened on Tuesday, June 12, 2018. How could I believe that it was possible when, only two weeks before, I had spent an evening with, among others, István Lovas – a distinguished author and journalist in Hungary – and he was full of energy, drinking, laughing, and speaking like a young man despite his 72 years? And still . . .

On Monday evening, he had not appeared on the Sajtóklub (Press Club) as usual. This weekly TV program, broadcast on Monday evenings, is aired on the Hungarian pro-government channel, Echo TV, and brings together four Hungarian journalists and publicists who comment on the news from Hungary and around the world. The show was created at his initiative at the beginning of the 2000s, and underwent several interruptions and revivals before becoming a fixture of the Hungarian television landscape.

Pista (István’s nickname), a historical pillar of this show from the outset, was very often the most independent and dissonant voice on it. He made no concessions and never feared to be tough, including towards the political family to which he was close. He nurtured the viewers with his analyses and information from across the world thanks to his voracious interest in international affairs, the ten languages that he knew, and his multipolar vision of the world, in which he maintained the same fierce opposition against unipolar Atlanticism as he had against Communism in the past. The latter had even earned him a prison term in Communist Hungary.

Pista is not there . . .

Monday evening. Sajtóklub. Pista is not there . . . I had thought that this might be due to the scandal resulting from a heated exchange he had had a few days earlier with the Hungarian liberal deputy, Péter Ungár, of the LMP (Politics Can Be Different) over the release of a statement by the party favoring the European Union’s sanctions against Russia.

Did he suffer from fatigue after this war of words? Did he decide to be a little more discrete for a few days? Did he receive instructions not to show up at the recording studio? These questions went through my mind. I had thought about calling him the following day, not knowing that he was already gone. Not knowing that “Lovas is dead.”

“Lovas is dead.” Even as this keeps going through my mind, these three words still sound surreal. I still feel that I will speak with him again very soon, exchanging news stories from around the world before he eventually hangs up, explaining to me that he has got hundreds of e-mails from dozens of press agencies all over the world which he has to answer. Or that I will see him again soon on TV, hearing him tirelessly denouncing the Atlanticists and speaking about opening up to the East, perhaps mentioning some anecdote about Singapore’s success, a country he liked so much that he mentioned it often, and he frequently went there. Or that we might soon share a bottle of red wine and a delicious ham at his home in Bicske.

The last time I had the chance to see Lovas, he regaled me with some anecdotes – some were funny, others were tragic – over his eventful life. He talked about his years in prison in the Hungary of the 1960s, about the way in which he managed to leave the country in the ’70s, about his work as a journalist for Radio Free Europe in the 1980s, and about the thesis he wrote at Sciences Po in Paris under the supervision of the famous historian, Hélène Carrère d’Encausse.

Pista is not there . . . he died on the battlefield

At that time I had no way of knowing that it would be the last time I ever saw him. I would have wanted to ask him so many things, to know so much more about this man and what he experienced over the past fifty years.

Pista was a workaholic and he worked up to eighteen hours a day, every day. Despite his age and the recognition he had already received, Pista was not the kind of man who rested for long. He tirelessly analyzed the news from everywhere, nurturing many press organs as well as his own blog. He was an army all by himself. And just as the ideal death for a soldier is on the battlefield, and that of the artist is on the stage, Pista died in his office, his head found resting on the keyboard of his computer.

His friend Zsolt Bayer, the host of Sajtóklub, declared after his death:

He did not live well. One who is in a state of permanent struggle does not live well. He was alone, he was solitary, he was combative . . . The combatant is always solitary and alone . . . And what is incredible is that, despite all of this, he was a good companion.

A good companion he was indeed. Many of the testimonies which followed his death, several of which came from colleagues who are much more younger than he was, emphasized the interest he had taken in the youth, and for the new generations of journalists in particular. In an age where many – especially in the individualistic Western world – think only about themselves in their twilight years, Pista was just the opposite. He was the sort who helped the young without expecting anything in return. A good example of this is that, from the beginning, he supported the Visegrád Post, which he read regularly and for which he had been about to write some occasional contributions. Its Editor-in-Chief, Ferenc Almássy, had always been able to count on his friendship and support.

Pistol Pista!

I gave István Lovas the nickname “Pistol Pista,” a reference to “Pistol Pete,” the nickname of the tennis player Pete Sampras.

Besides being a workaholic, Pistol Pista was known for his outbursts – sometimes against the Americans, sometimes against such and such Hungarian official whom he believed was not doing a good job.

-

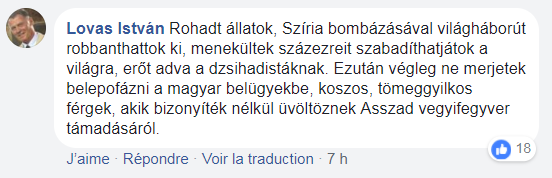

“Bastards, you might start a World War with your bombing of Syria – provoking hundreds of thousands of refugees from around the world while reinforcing the jihadists! After that, do not dare to ever again open your mouth about Hungarian internal affairs, you dirty, mass-murdering worms who cry without any proof about Assad’s chemical attack!” This was a comment that Pistol Pista had left on the Facebook page of the American embassy in Budapest.

As for his habit of getting into arguments, he was banned for one year from entering the European Parliament (where he had worked for several years as a press correspondent) after having sent an inflammatory letter to the Dutch liberal MEP, Sophie in’t Veld. Upon learning of this, Pistol Pista declared that he wanted to appeal this decision, as he considered that he had merited a lifetime banishment from the institution.

István Lovas was not only “Pistol Pista,” but it was an important part of his personality, and by offering some examples, I want readers who do not know Hungarian to get to know this aspect of the giant.

An immense void and a legacy

István Lovas will leave an immense void behind him. As Zsolt Bayer asked, who could replace such courage, such capacity for work, such broad knowledge of languages and facts? Even a team of five to ten people could not easily replace him.

Frigyes Fogel, an independent film producer, had undertaken the production of a documentary film about his life. Lovas told him, “There has never been a film about me before, and nothing about me will remain when I die, so I would be very happy if we can make this film.” Alas, only a single interview was completed before his death. The others were to be conducted after the April elections. They never were. So Fogel published the first interview.

Does this mean that István Lovas will leave nothing behind, as he feared? Let’s try to prove Pista wrong.

Pista is someone who left a legacy behind him. These are several generations of Hungarians who remember him for different reasons. I have already written about how much the young journalists appreciated Lovas. But following the announcement of his death, the entire Hungarian press published obituaries. All the well-known writers and pundits offered homages. Sure, sometimes they criticized his politics, but everyone liked him. To all of them, he embodied a combative, correct, and exemplary style of journalism, one of integrity. And as many pointed out, he was an inspiration to several generations of Hungarian journalists, even those who held different political viewpoints.

Those Hungarian patriots who are 35 and older remember those difficult years following the electoral victory of the liberal Left in 2002, including when Sajtóklub itself was forced off the air and its hosts – Lovas among them – were subjected to intense political pressure. Eventually, the show was revived on other, lower-profile channels, and Lovas began every broadcast by saying, “We have still X weeks left until the next parliamentary elections.”

Likewise, those of all ages who love Hungary’s freedom, a freedom that has become severely restricted within the mechanisms of the EU and NATO, will always remember Lovas’ tireless courage in never failing to condemn Atlanticist warmongering. Lovas had always been hostile to the Western world, a world that he knew well, in many ways better than those of his countrymen who had remained at home throughout the Communist dictatorship. He was criticizing the West from an illiberal perspective, and in favor of an alliance with China or Russia long before these ideas were integrated into the program of Fidesz and Viktor Orbán, something which Lovas was very happy about when it did happen.

Lovas was also one who, despite his argumentative nature and staunch positions, was fundamentally an open-minded man who welcomed dialogue. To cite but one example, although he had been an extremely vocal and combative anti-Communist who had been imprisoned by the Communist regime in his youth, he held Mr. Gyula Thürmer, who has been the leader of the Communist Hungarian Workers’ Party since the regime change, in high regard, because unlike most of those old Communists who quickly converted to the gospel of liberal capitalism (and who in turn used this to squander and divert en passant large amounts of the national wealth of the country into their own pockets), Thürmer always remained loyal to his convictions.

Goodbye, Pistol Pista!

Pista, I will miss you. Hungary will miss you, and all those who are still so reckless as to believe in a free Hungary and in the possibility of a more balanced world will miss you. The Hungarians have the habit of believing that their loved ones keep an eye on them from the Hereafter. This idea coexists with the legend which holds that the Milky Way represents the armies of Csaba, Attila the Hun’s son, which stand ready to come and help the Szeklers, the Hungarians of Transylvania at the borders of the Carpathians, in their hour of need.

You were an army unto yourself, Pista. Keep an eye on us from where you are now. Goodbye, Pistol Pista, goodbye, Mr. István Lovas!

Translated from French by the Visegrád Post.