By the editorial board of the Visegrád Post.

Visegrád Group – As everywhere else in the European Union, turnout in the European election has been low in the V4 countries. However, in each of the four countries of the Visegrád Group, the 2019 European election reached a record participation, as shown in the table below:

| Hungary | Slovakia | Czechia | Poland | |

| 2019 | 43,37 | 22,74 | 28,72 | 42,96 |

| 2014 | 28,97 | 13,05 | 18,20 | 23,83 |

| 2009 | 36,31 | 19,64 | 28,22 | 24,53 |

| 2004 | 38,50 | 16,96 | 28,32 | 20,90 |

Turnout in percent, per country and per year, in the European elections.

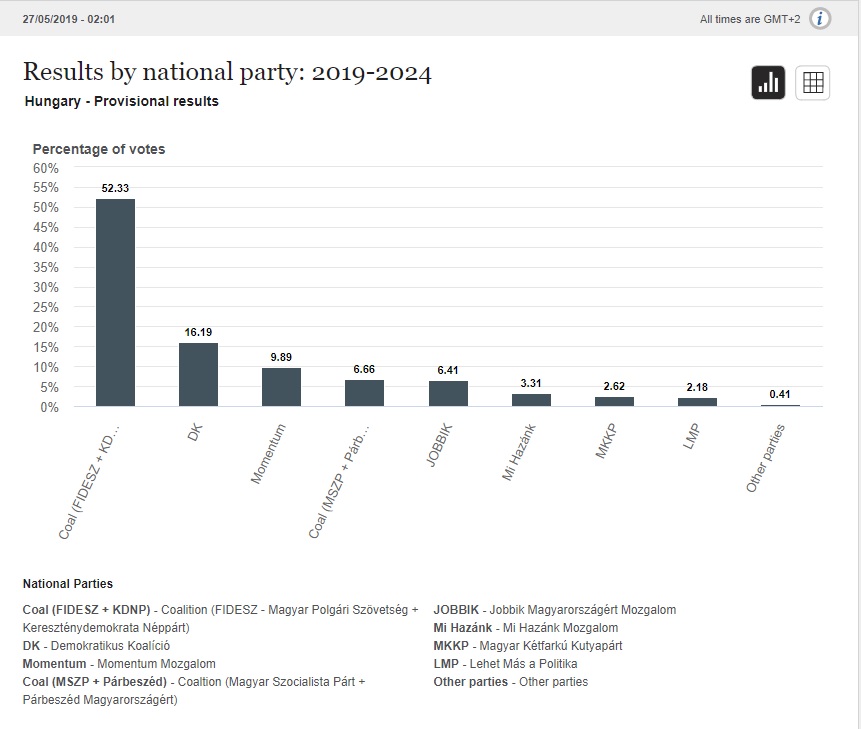

Hungary

Crushing and unsurprising victory of Fidesz, the national-conservative party of Viktor Orbán, with 52.30% of the vote. For the Hungarian Prime Minister, in an open war with the liberal world and the Brussels elite, this absolute victory offers him once again an argument of democratic legitimacy to continue his policy — anti-immigration, pro-Christian, pro-family — and become more involved in politics on a continental level. Indeed, his contingent of 13 deputies may, whether they stay in the EPP or not, be useful to him as a negotiating argument. The Fidesz MEPs are, after the Maltese Labor MPs, the elected members of the European Parliament for 2019-2024 enjoying the higher percentage of votes.

In second position, the DK of former Prime Minister Ferenc Gyurcsány, a politician in favor of the United States of Europe, who is a highly controversial figure of Hungarian politics for his bloody repression of the riots of autumn 2006. This liberal leftist politician is often criticized as an indirect objective ally of Viktor Orbán, since some see him as an element of discord in the opposition – however very disunited with or without Gyurcsány.

In third place, Momentum, the new liberal party allied to Emmanuel Macron and Guy Verhofstadt, after a meteoric rise. This party often mocked as being a party in downtown Budapest managed to make a breakthrough especially in some secondary cities.

In fourth and fifth positions, the Socialist Party and Jobbik, side by side, succeeding to have each one an MEP. Both parties are experiencing a dangerous decline for their survival, by the admission of their own executives. Read our special report on the evolution of Jobbik by clicking here.

Among the parties that do not get any MEP (scoring below 5%), László Toroczkai’s new nationalist party, Mi Hazánk, the MKKP, the satirical and anarchist party, but especially the LMP, the green-liberal party that suffers a potentially fatal blow; its leadership even resigned following the announcement of the results.

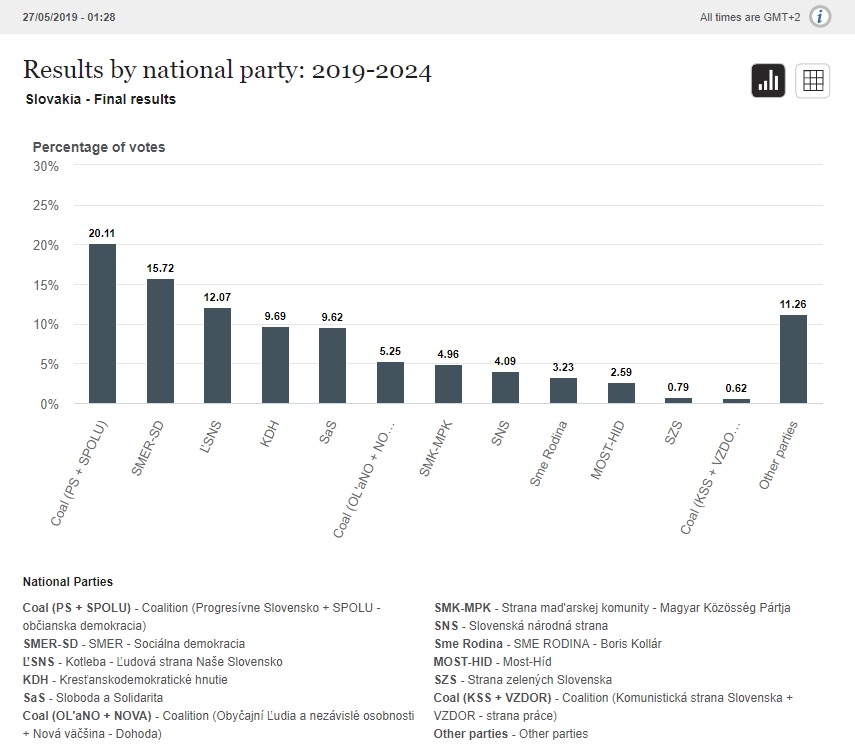

Slovakia

In the wake of the recent presidential election that brought the 45-year-old liberal lawyer Zuzana Čaputová to become head of the state, the European election in Slovakia saw the victory of the coalition gathering Progressive Slovakia (Progresívne Slovensko) and Together-Civic Democracy (SPOLU – občianska demokracia) with barely more than 20% of the votes. This new victory for the liberal forces could mark a turning point in Slovak politics.

In second position, the SMER, the party leading the government coalition led by Prime Minister Peter Pellegrini, successor to Robert Fico, who is a strong figure of Slovak politics. A score of 15.72% which pales in a context of distrust. The fragmentation of the Slovak citizens’ vote also shows the degree of political instability that is currently shaking the country.

In third place, the radical nationalists of Marian Kotleba, which was quite unexpected whereas following the regional elections of 2017, many thought them on the decline.

Side by side, the Christian Democrats of the KDH and the liberal-libertarian and eurosceptic party SaS, reach almost 10% each. The declining KDH, however, maintains its two MEPs while the SaS, which switched from the liberal ALDE group to the conservative Eurocritic group ECR in 2014, shortly after the elections, strengthened by 3 points.

The coalition of Ordinary People and Independent Personalities (OL’aNO) and New Majority (NOVA), a sort of illegitimate child of the KDH and the SaS, gets an elected representative.

Notably, the party of the Hungarian minority in Slovakia, close to Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz, just fails for the minimum 5% needed to have a MEP. This can mark the beginning of the decline of the minority vote.

Among other parties not getting the 5% is the patriotic party SNS which continues its decline and the liberal party Most-Híd (a party with merged from the Hungarian minority party MKP but wishing to be “trans-national”), whose electorate was probably captured by Zuzana Čaputová.

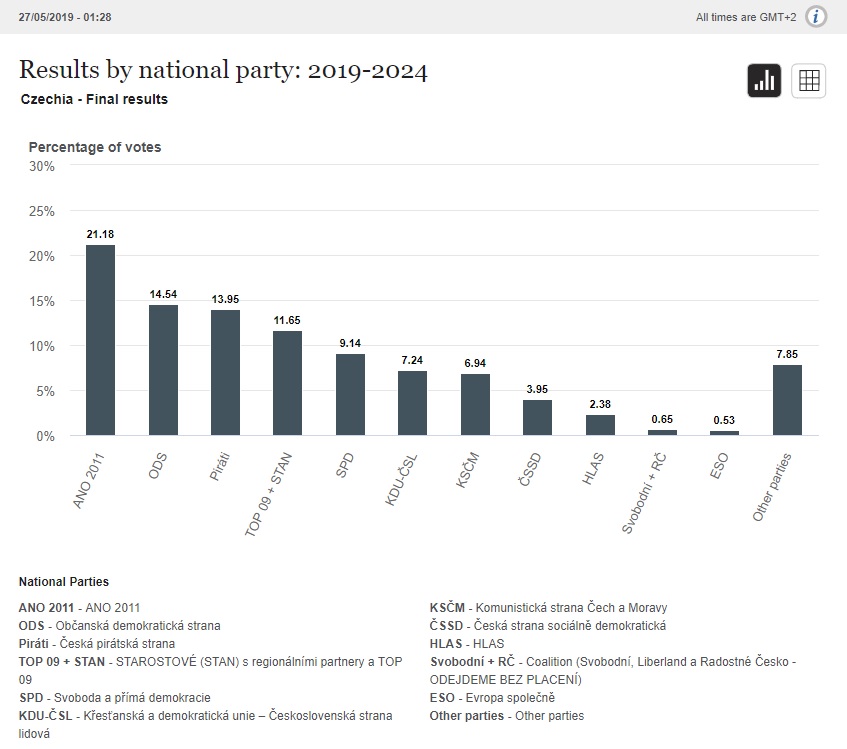

Czechia

ANO 2011, the party of Prime Minister Andrej Babiš managed to win this election, despite the constant attacks against him. ANO 2011 even improved its score compared to 2014, when the liberal-conservative party won 16.13% of the vote. A breath of fresh air for the billionaire Prime Minister, a businessman known to have a great sense of humour, entered politics in order to break the codes and improve the economic management of the country according to a more economically liberal vision. Key player in the strengthening of the V4, Andrej Babiš, whose party is theoretically a member of ALDE – like Macron’s LaREM! -, however, stands fiercely opposed to mass immigration, the euro and the strengthening of the Paris-Berlin axis.*

In second position, the liberal-conservative and eurocritical ODS party, a historical heavyweight of Czech politics. With four MEPs, and member of the ECR group, it can be an objective ally of Babiš on the European level to defend the Czech interests.

The pirate party confirms its position as the country’s third political force. This liberal progressive party is supported by a generation that has become politicized with the internet, feeling concerned by issues related to the digital topics, in favor of a more direct democracy and integrated into the ideology of “open society”.

In fourth place, TOP 09 (“Tradition, Responsibility, Prosperity”), a liberal-conservative party, a member of the EPP, maintains a key presence in Czech politics, albeit with a slight decline from four MEPs to three.

In fifth place, the party Liberty and Direct Democracy, SPD, of Czecho-Japanese businessman Tomio Okamura. This patriotic, anti-Islam, anti-immigration and highly EU-critic party joins the ENL group in the European Parliament with two elected representatives.

The Christian and Democratic Union – Czechoslovak People’s Party comes sixth. The KDU-ČSL, a Christian-democratic party, member of the EPP, loses an MEP and will send only two MEPs to Brussels.

Finally, the Czech Communist Party — which remained on a Labor and Marxian line, and thus opposed for example to immigration in order to protect Czech workers — still remains above the 5% mark, despite a gradual decline.

As in Slovakia, the Czech political landscape is very fragmented and diverse. This is due in particular to a lasting crisis in the Czech political system.

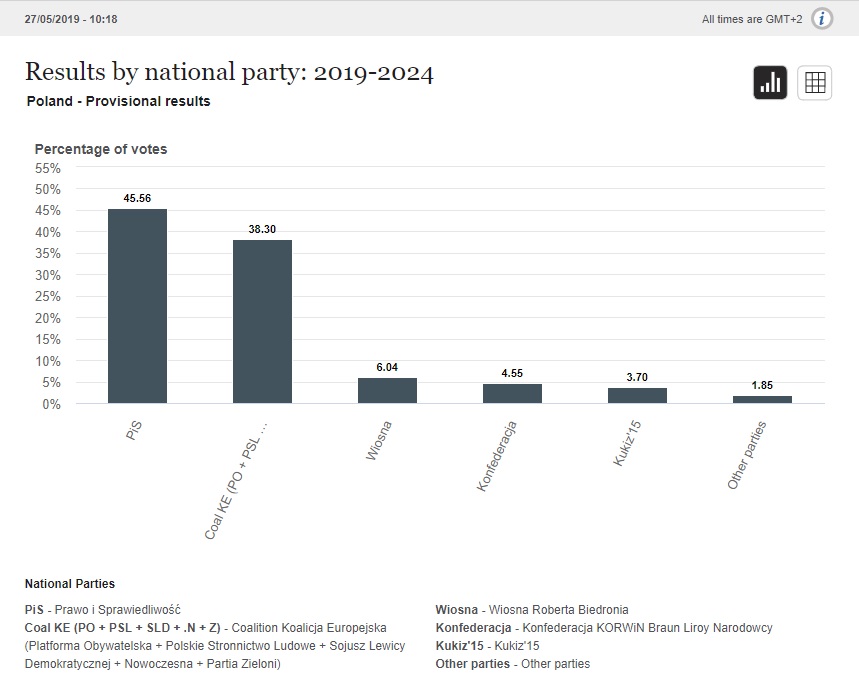

Poland

In Poland, first PiS victory in a European election, improving its score compared to 2014 (+ 13.78%). The national conservative party in power since autumn 2015 was counting on these elections, six months ahead of the legislative elections, to measure its ability to mobilize. It’s done and the result is more than satisfactory for the PiS. Encouraged by this result in their policy on a European scale, the PiS, leading party of the ECR group, intends to be heard more than ever in Brussels.

In second position the European coalition of the PO, left-wing liberals and members of the EPP, as well as the liberals-libertarians of Nowoczesna, the PSL agrarian party, the post-communist SLD social-democrats and the Greens. This means the failure of a united front policy that is worrisome for opposition forces ahead of the legislative elections this autumn. However, the gap is not very important between the European Coalition (KE) and the PiS, constituting two major blocks in Polish politics.

In the third position, the brand new Spring (Wiosna) movement of LGBT activist Robert Biedroń. A non-negligible score for this radical progressive party, founded in February 2019, and defending an LGBT and pro-European line. Everything seems to indicate that this movement, structured around LGBT political activism, can become a permanent itch for the Catholic and conservative PiS.

In fourth place come the patriots of Konfederacja, a motley union of nationalists around the sulfurous libertarian monarchist Janusz Korwin-Mikke, known for his provocative outings on women, democracy, the Third Reich and the European Union.

The Kukiz’15 movement falls like a soufflé, not reaching the symbolic threshold (in Poland, as in the United Kingdom, the system integrates a measurement by regions) of the 5% and thus risking to leave the Polish political landscape soon. They do not get any MEP.