By Ferenc Almássy.

Central Europe – One of French President Emmanuel Macron’s campaign promises was to take action against the “social dumping” caused by workers from “Eastern Europe.” In the view of the pro-European candidate, this situation has arisen primarily due to a “bad attitude” towards the European Union among its eastern members. In particular, Poland was explicitly targeted and even threatened during the French presidential campaign by Macron.

From August 23 to 25, Emmanuel Macron visited Austria, Romania, and Bulgaria to meet with various heads of state or government to address the issue of reforming the EU’s labor laws. According to some observers, Macron was trying to exploit the chaos being generated by the migrant crisis and the upcoming elections in Germany to gain an advantage in Central Europe and find new allies there in order to build a “Little Entente” for the present day. In this view, Europe is in the midst of restructuring after Brexit and Trump’s election, causing the Anglo-Saxon world to become distanced from the EU and giving Macron the golden opportunity to seize moment for France.

But this is not the case. German Chancellor Angela Merkel will be re-elected, American lobbyists still dominate in Brussels, and above all, Macron has obligations to Berlin. Emmanuel Macron, the “new boy” as Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán called him, only came to do Berlin’s dirty work, given that Germany is currently preoccupied with its domestic politics in the weeks prior to its elections. His task was to divide Central Europe by looking for those he might be able to seduce with his puppet show.

Destabilizing the Visegrád Group was one of the goals of Macron’s trip. Warsaw and Budapest were not on the French President’s itinerary despite their major importance to the region. The message is clear, and Central Europe’s news media has not been fooled. The current resident of the Élysée, acting on behalf of the EU’s hardcore leadership, sought to divide and conquer. It was a failure, however.

The Summit of Salzburg: A Half-Victory that Didn’t Lead to Anything Concrete

Macron began his trip by meeting with the leaders of the Slavkov Triangle (Austria, Czechia, and Slovakia) in Salzburg. Recently, Slovakian Prime Minister Robert Fico said that even if he agrees with the Visegrád Group on many issues that Slovakia, as a member of the Eurozone, belongs with the “core of the EU, France and Germany.” As a token of goodwill, Fico even accepted some displaced migrants. It may have been coincidental, but this happened roughly concurrently with the end of his government’s alliance with the patriotic Slovak National Party.

The leaders of the Slavkov Triangle are all social democrats, and Fico has shown signs of rapprochement with Western Europe. Consequently, the terrain seemed favorable to Macron. However, the discussions regarding the issue of posted workers, which had been announced as the focus of the meeting, did not end in consensus, although the four leaders agreed on the need to resolve the issue of wage disparities.

Fico and Czech Prime Minister Bohuslav Sobotka began by rejecting en bloc the proposal to include discussion of road freight in the meeting. Fico also pointed out that Poland and Hungary, two countries who both have among the highest number and percent of posted workers in Europe, will refuse to sign anything which aims to centralize reforms in Brussels’ hands. None of the eleven countries in the eastern zone of the EU will accept a solution in which Brussels dictates salaries.

Upon his return home, Fico explained in a statement to the press that he does not accept the document which lays out the “à la Macron” directives, as this would undermine the competitiveness of Slovak entrepreneurs.

Sobotka had a similar reaction to the meeting. “If France, Austria, and other countries are talking about social dumping and about our workers being ready to work for low salaries, if we compare it to their own labor market, the low salaries are also due to their firms economizing in Czechia,” he said, referring to Western European factories that have been relocated or implanted there. Sobotka later reiterated in an interview that Czechia will not accept migrants, especially not Muslims. This was a way of reminding the EU that the issue of migration is not negotiable, despite Merkel’s and Brussels’ efforts, which are now being supported by Macron.

The agreement in principle between the four leaders was seen by some in the press as half a victory for Macron who, even if nothing tangible was accomplished, at least managed to persuade all of them to agree on the necessity for collaboration on this issue. The problem is that Fico, a populist who is facing growing domestic opposition, might well change his mind when the wind changes – again – while Social Democrat Kern will most likely be replaced by Sebastian Kurz, who has begun leaning increasingly to the Right in recent years, and could potentially form a coalition with the Euroskeptics of the Austrian Freedom Party.

In the meantime, Sobotka promised Macron a four-year partnership between Paris and Prague. But it is almost certain that the Czech PM will not succeed in the October elections; it could very well be the billionaire Euroskeptic Andrej Babiš who wins. Therefore, any strategic planning being made by Sobotka may well fall apart in the very near future.

Romania and Bulgaria: The Free Market First

At Macron’s next stops in Romania and Bulgaria, he had a strong argument: his support for their admission to the Schengen Zone. The French head of state said, “Romania has had the right to request its integration into the Schengen area for years now.” But this wasn’t enough to tilt Romanian President Klaus Iohannis in his favor, who at the joint press conference declared himself neutral regarding Macron’s proposal.

In principle, Iohannis and Bulgarian President Rumen Radev agreed with Macron that they must intensify their efforts against the abuses committed by the use of posted workers, but they explicitly refused to touch the rules of the free market. Even worse, Iohannis expressed his disagreement with the implementation of the EU labor reforms that Macron has called to be enacted by January, in spite of the fact that young French President had announced this as his goal. Macron stated, however, that he remains confident.

Romania committed to purchasing military helicopters and anti-aircraft missiles from France, which recently opened an Airbus Helicopters Group plant near Brașov. Also, Airbus is extending its exclusivity contract with the Romanian aircraft manufacturer Romanian Aeronautic Industry from five to fifteen years in exchange for the delivery of fifty helicopters to Romania over the next ten years.

As for Bulgaria, the country will assume the presidency of the EU Council in January 2018. As it is opposed to Macron’s plan, this reinforces the pressure on the French President: his last hope to pass his reforms is at the European Council’s meeting on October 23.

Poland: The (not so) Surprise Guest

Although Macron did not visit Warsaw on this trip, Poland was nevertheless at its heart. Poland’s Prime Minister, Beata Szydło, promptly issued her administration’s position regarding the reform of the posted workers’ directive. She made it clear that, for the conservative government of the Law and Justice Party, the reforms proposed by Macron are unacceptable, and that they will go “all the way to the end” in their opposition. And this confrontation includes already the European Commission.

It seems clear that Macron sought to provoke a diplomatic incident via the press in order to give more consistency to his journey. On Friday, during his speech in Bulgaria, Macron responded by stating that Poland was a “country that has decided to go against European interests on many issues, and a state which has decided to isolate itself,” adding that it is ” another mistake” from Warsaw, which he believes has been “sidelined ” by Europe on “many issues.” “Europe has been built to create unity. It is the very meaning of the structural funds that Poland accepts,” he threatened.

But the worst was yet to come. “Poland by no means defines the course of Europe,” Macron continued. “The Polish people deserve better than that.” He went on to say that “Europe has been built on values which Poland is today opposing.”

Needless to say, Poland did not tolerate such remarks. “Perhaps his arrogant statements are due to his lack of political experience and practice, which I can understand, but I expect that he will soon catch up with these gaps in his knowledge and that, in the future, he’ll be more reserved,” Beata Szydło told reporters. “I advise the President to take care of the affairs of his own country. Maybe then he will succeed in attaining the same economic results and the same level of security for his citizens as those that are guaranteed in Poland.” She went on to remind Macron that “Poland is a member of the European Union in the same way that France is,” and called on him to “remain more conciliatory and not break the EU apart.”

Failure and Masquerade

Macron succeeded in selling helicopters and missiles, but for the moment he has no new allies in Central Europe apart from the appointed Austrian Chancellor, Kern, who will likely be replaced in less than two months. Worse, he appeared arrogant to all those countries which, although they sometimes have divergent viewpoints and interests, all share one fact in common: they are the “countries of the East” that were betrayed in the twentieth century and which have been despised ever since; having recently escaped from totalitarianism and now looking for freedom, they are eager to do away with their “economic backwardness” and catch up with the West.

This was therefore a failure for the French President, whose ambition was to “re-found Europe” in order to prevent its breakup and a “dismantling of the European Union.” His reform proposals faced frank opposition from some of his target countries and yet received no equivalent support in the region. Passing these reforms by the end of the year, which is Macron’s objective, seems to be extremely unlikely at the moment. However, Macron appears to remain confident and says he is looking forward to the meeting of the European Council in late October. “By October, we will finalize the agreement that will lead to a positive solution for everyone . . . And it is a possibility, according to the ambitious terms put on the table by France.”

An observer might question the meaning of this tour and this forced debate over the question of posted workers, which has been seen by the press in many countries of Central and Eastern Europe (CEEC) as a distraction aimed at making people forget France’s own burgeoning problems, as well as to raise Macron’s popularity rating, which is currently lower than François Hollande’s was at the beginning of his term. Indeed, opposition to European posted workers would seem to contradict the EU’s extremely generous migration policy towards non-Europeans. It makes some sense, however, given that the specter of Brexit and the pressure of protectionist forces have been hanging over and influencing the policies of the French government. If one were to talk about social dumping, it would therefore seem to make more sense to begin with the nearly 300,000 immigrants, both legal and illegal and mostly from Africa, who enter France every year.

It is also interesting to look at the figures. Posted workers represent 0.7% of the European labor force. In France, only Poles represent a large contingent of posted workers from Eastern Europe; they represent 17% of this workforce, mainly concentrated in the construction sector.

Whatever the case may be, if the European Commission rejects the amendments, Macron still has the option for the European Council to vote on it unanimously. This is of course unlikely, given the positions of some member states. But if the European Parliament modifies the text, it can then refer it to the European Council, where the text could be adopted by a simple majority of votes.

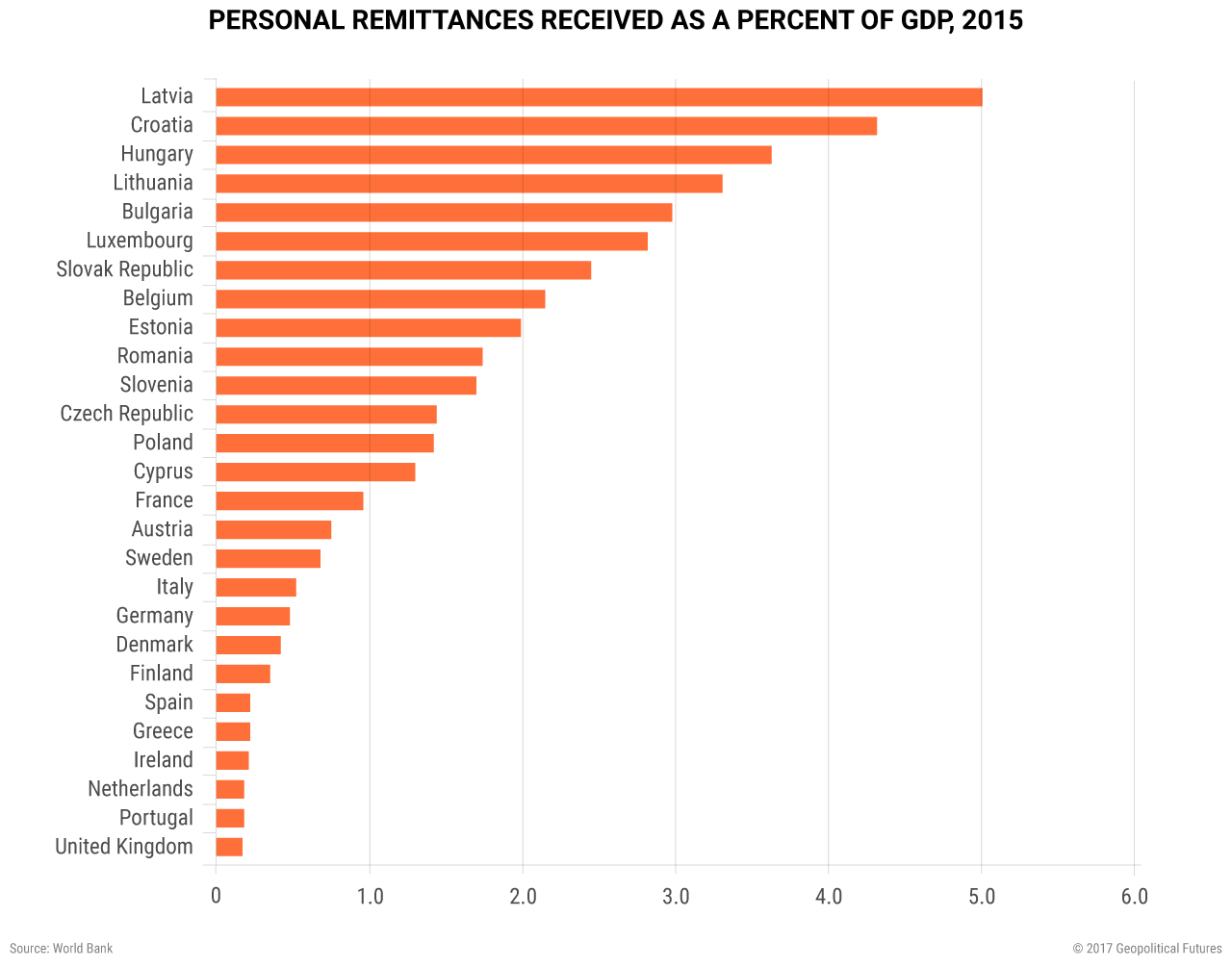

It is crucial for the CEECs to retain their ability to define their own wage rules. In the perverse system of the EU, it is the only way for them to compete with the economic giants of the West. It is also a considerable source of income for them at present.

The “two-speed Europe” is becoming more real. Macron’s threats, which came in the form of a warning allegedly for the sake of the common good and the highlighting of European funds and the sustainability of the European Union, show the importance of the crisis ahead. The divide between the West and the East has not been resolved and the economic gap between the two parts of the continent, which has been structurally affirmed by the EU, is now leading to a situation of unprecedented tension within the EU project.

Somehow, the West will have to opt for some form of protectionism, and this will reinforce the “two-speed Europe” that the EU’s hardcore founders desire and which will reject the needs of the CEECs as a whole.

If things continue in this way, it is quite possible that the Visegrád Group and/or the Three Seas Initiative will become more formalized and develop new tools which will enable this peripheral Europe to stay in the race, after his Western brothers have once again betrayed him.