By Olivier Bault.

Poland – A constitutional majority no longer seems to be completely out of reach for the Law and Justice party (PiS). Is it possible, though, under Poland’s proportional representation system? The D’Hondt method, used to calculate seats allocated in the Sejm, certainly gives an advantage to the winner at the redistribution of votes from parties and coalitions which have not reached the threshold for entering parliament, which is 5% for single parties and 8% for electoral coalitions. It was this mechanism that allowed the United Right, an electoral coalition formed by PiS and two small right-wing parties, to secure an absolute majority in the autumn of 2015 after receiving 37.5% of the popular vote. In that election, the United Left coalition, a far-left party and a liberal-conservative party provided a significant reservoir of votes to be redistributed, as they did not reach the electoral threshold. For the next parliamentary elections, which will most probably take place in October (the exact date has yet to be announced), the leftist-liberal European Coalition (KE) formed before the European elections has broken into three electoral coalitions, and if two of these three blocks fail to reach the required threshold, then a constitutional majority could be close at hand, and that is what is truly at stake today. For after the very clear victory of PiS in the European elections of May 26, few commentators still doubt that its absolute majority will be renewed.

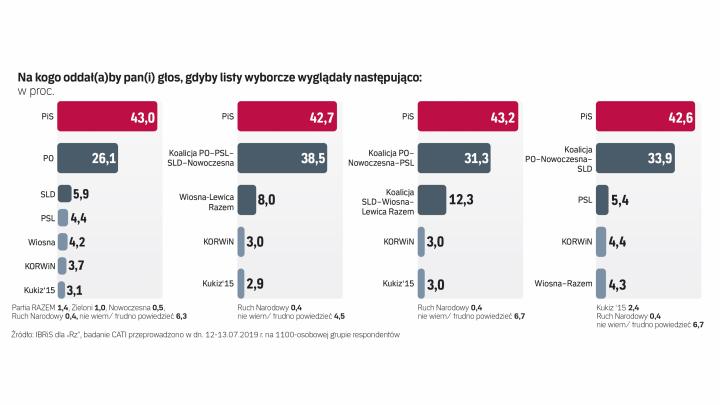

A survey published by the Rzeczpospolita daily on July 17 showed, however, that PiS could be one seat short of an absolute majority should the European Coalition re-form to contest the next parliamentary elections, with 42.7% of the predicted vote going to PiS, 38.5% to KE and 8% (just at the level of the threshold) to a possible coalition of the pro-LGBT Wiosna (Spring) party and the far-left Razem Lewica (Left Together) party. On the other hand, with a divided opposition, the same survey showed that, with 43% of voters choosing PiS, the shares of the vote going to the former members of the European Coalition would be as follows: 26.1% to Civic Platform (PO, the liberal party of former PM Donald Tusk), 5.9% to the post-communist SLD and 4.4% to the PSL agrarian party.

For the PSL, whose rural voters are rather conservative and mostly Catholic, the decision to create a centre-right Polish Coalition, which is supposed to be inspired by Christian-Democratic ideas, was taken just after the defeat of May 26, in an effort to bring back the party’s traditional voters who had been driven away by the liberal-progressive, anticlerical and openly pro-LGBT shift inflicted on the European Coalition by the left, with the consent of the liberals of Civic Platform, as those voters had clearly preferred to vote for PiS. It remained to be seen whether the formerly Christian-Democratic PO, which stems from the left wing of the legendary anti-communist Solidarity trade union, would remain in a coalition with the SLD’s post-communist social democrats. Among PO members and local political leaders, not all approved of such an alliance. The liberals finally took their decision on July 17: the alliance with the post-communists will not be renewed for the parliamentary elections.

Next autumn, PiS will therefore face three competing opposition blocks:

– The most important, formed by Civic Platform and the leftist-liberal Nowoczesna (Modern) party along with a pro-abortion feminist movement, has again adopted the Civic Coalition (KO) label which worked relatively well in regional and municipal elections last autumn, and it has confirmed its progressive shift, including a promise to introduce civil unions for homosexuals. PO no longer really has a choice anyway, even if such a change is ammunition to Jarosław Kaczyński’s PiS, which thus gains a chance to attract the moderate centre-right electorate, while the nationalists, liberal-conservatives and pro-life Catholics on its right remain too weak to be a source of concern. Indeed, in the absence of a charismatic leader (there is only the dull and clumsy Grzegorz Schetyna, who has demonstrated, on the issue of civil unions for example, that he is able to say one thing one day and the opposite the next) the main faces of PO in the media today are the mayors of Gdańsk and Warsaw, with their “LGBT charters” and their tendency to behave as a “total” opposition standing against central government.

– To the right of KO is the Polish Coalition, formed by the PSL, whose credibility has suffered greatly from its membership of the European Coalition. As long as Władysław Kosiniak-Kamysz remains leader, it will be difficult for that party to convince voters that it is again conservative and attached to Christian values. The PSL is holding discussions with the national-conservative Kukiz’15 party with a view to its joining the Polish Coalition. Previously, its leader Paweł Kukiz had compared the PSL to an organised crime syndicate.

– To the left of KO is a coalition of the far left, bringing together the post-communist SLD and the LGBT activists of Wiosna, as well as the far-left Razem Lewica, whose leader once said that the SLD could not claim to be left-wing and was part of the same neo-liberal establishment as PO and PiS.