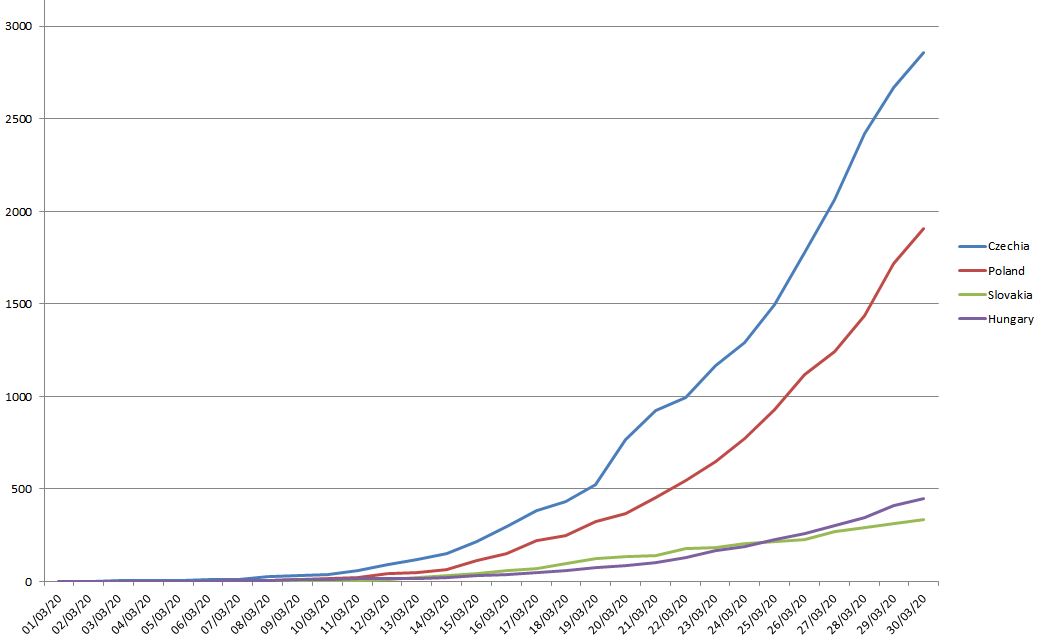

Visegrád Group – The first country of the Visegrád group to confirm cases of COVID-19 on its territory was Czechia on March 3. The remaining three countries quickly followed suit, as many people were returning from their winter holidays in such places as northern Italy, Austria and Germany. Poland had its first case on March 4, Hungary on March 5 and Slovakia on March 7. Hence March 3 is the date since which the epidemic has made progress every single day in the V4 taken as a whole: from three cases on March 3 to six cases on March 4, eight on March 5, 15 on March 6, 23 on March 7, 42 on March 8, and so on. There were 70 confirmed cases of COVID-19 in all four countries by March 10, 401 by March 15, 1,354 by March 20, 2,866 by March 25, and 5,547 by March 30, with many new cases being diagnosed every day, due largely to the ramp-up in testing and the return of nationals from abroad. By March 30, the Visegrád Four had conducted over 110,000 tests for the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus in total, including about 46,600 in Poland, 43,500 in Czechia, 13,300 in Hungary, and 7,500 in Slovakia.

The population of the Visegrád Group taken together is roughly equivalent to that of Italy (60.3 million), France (67 million) or the UK (67.5 million). With 38.4 million people in Poland, 10.6 million in Czechia, 9.8 million in Hungary and 5.5 million in Slovakia, the total for the V4 is 64.3 million.

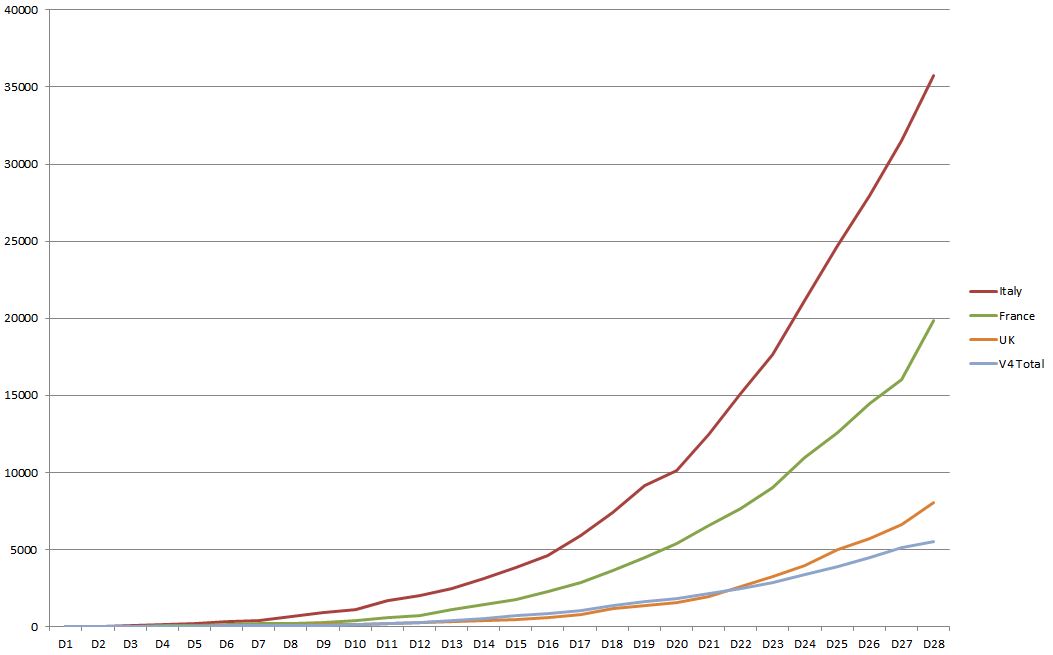

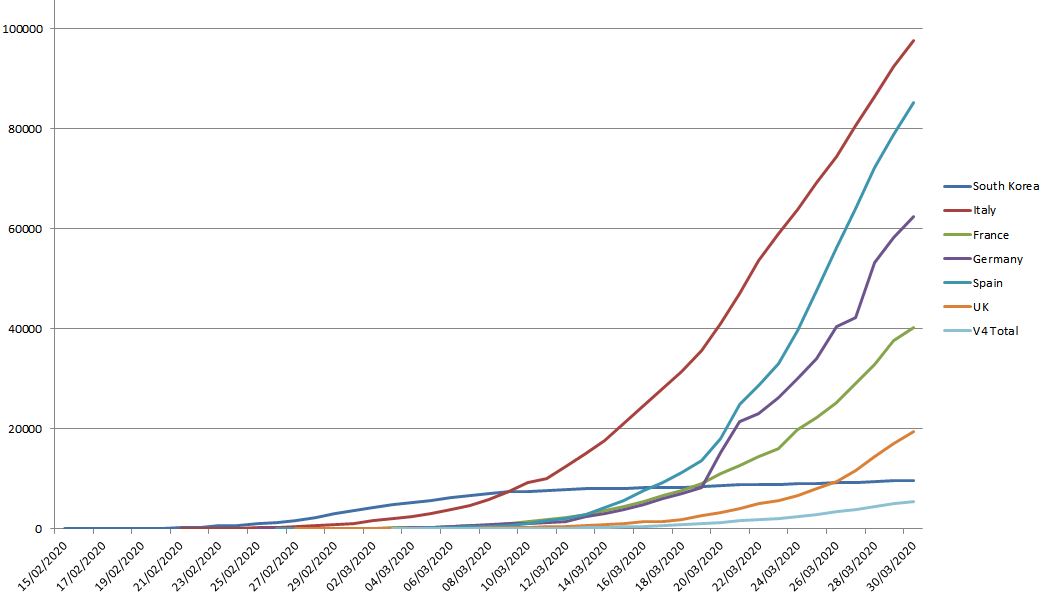

Although the evolution of the pandemic is extremely dynamic and things could change fast either for the better or for the worse, by the end of March it was becoming clear that the decision taken by all four countries of the Visegrád Group to take strong measures at an earlier stage of the epidemic was having some effect, with its progression continuing to be linear and not exponential. Starting from the date when the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases began to increase daily, one can easily compare the rise in cases from Day 1 to Day 28in different countries (March 30 is the 28th day of the epidemic in the V4). For Italy, Day 1 means February 21, for France it means February 26, and for the UK it means February 27. These are not the dates when those countries registered their first cases, but the dates since which new cases have been reported every single day. While on Day 28 of the epidemic the Visegrád Group as a whole had 5,547 confirmed cases (on March 30), Italy had35,713 cases (on March 19), France had 19,856 (on March 24) and the UK had 8,077 (on March 25), with the gap widening day by day.

Number of deaths by Day 28 of the epidemic:

2,978 in Italy (on March 19), 860 in France (on March 24), 422 in the UK (on March 25), 69 in the V4 (on March 30)

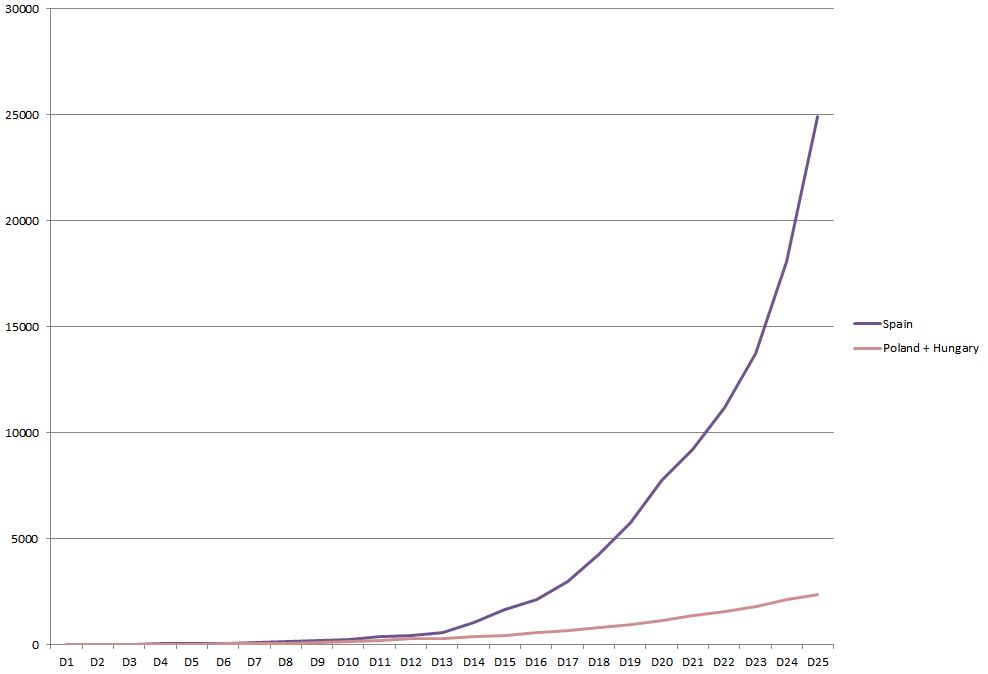

That gap is even more striking when we compare Poland and Hungary (48.2 million inhabitants in total) with Spain (46.7 million inhabitants), where Pedro Sánchez’s government was particularly reckless in handling the disease, as it chose to hide the real numbers of confirmed cases in Madrid to enable the March 8 radical leftist and feminist marches to take place all over Spain, with minister for equality Irene Montero (from the far-left party Unidas Podemos) leading the Madrid march before being tested positive for coronavirus four days later. The number of confirmed cases started to rise daily in Spain on February 26, when Italy was already losing control over the epidemic, with two cases in Spain and 1,261 in Italy on February 26, 12 cases in Spain and 1,766 in Italy on February 27, 25 cases in Spain and 2,337 cases in Italy on February 28, and so on. Therefore, by the end of February Spain could have drawn conclusions from what was happening in Italy, just as the V4 countries did from what was happening in Italy, Spain, France, the UK, Germany and other countries of Western Europe when they had their own first confirmed cases at the beginning of March. In fact, the Spanish authorities allowed and even encouraged huge marches on March 8, with some 120,000 women marching together in Madrid alone, just two days before the V4 countries began to announce that they were cancelling all mass events and closing schools and all cultural venues! Furthermore, Spain closed schools at national level from March 13 only (some of its autonomous regions, like that of Madrid, had done so earlier, causing a massive exodus to the sea coast) – this was later than Poland, Czechia and Slovakia, and just one day before Hungary, where there were only a few dozen confirmed cases compared with a few thousand in Spain (2,965 as of the morning of March 13).

Starting from February 26 in Spain and from March 6 in Poland and Hungary, here is how the epidemic evolved during the first 25 days (up to March 30 for Poland and Hungary, up to March 21 for Spain):

Number of deaths by Day 25 of the epidemic: 1,326 in Spain (on March 21) and 41 in Poland+Hungary (on March 30)

However, Spain is not the only Western European country where the epidemic was allowed to develop before national authorities stepped in. One factor is that for ideological reasons national governments refused to close their borders with Italy after having failed to ban travel to and from China after January 20, when the Chinese leader Xi Jinping informed his people and the world of the real extent and seriousness of the COVID-19 epidemic, which communist China had first tried to keep secret and then to make appear less serious than it really was. For example, on February 26, when there were already several hundred confirmed cases in northern Italy, France allowed some 3,000 Italian supporters to come freely from Turin to Lyon for a football match between Juventus and Olympique Lyonnais, in spite of several opposition leaders asking PM Édouard Philippe to have the event cancelled. The irony of the situation is that the Chinese authorities had not themselves hesitated to completely isolate the city of Wuhan and the Hubei region, home to some 59 million inhabitants, so that for China the bulk of the confirmed cases have so far been located in that region. As a consequence, by the end of March it was the Chinese who were shutting down air connections with other countries to protect themselves from a return of the epidemic they had let spread abroad and managed to control at home. France went even further, allowing the first round of local elections to take place on March 15, while already having 4,469 confirmed COVID-19 cases on that day, only to hear President Macron announce a general lockdown on the following day, with the second round of the elections being postponed to June! A week later, a number of election volunteers started to show symptoms of COVID-19 and tested positive for the coronavirus.

Some countries, like the United Kingdom, the Netherlands and Sweden, officially chose to let the epidemic develop on their territory, albeit trying to slow it down, to let their population acquire so-called herd immunity – that is, to reach a point where a sufficiently large part of the population would become resilient to the new SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus so that it could no longer spread so easily. Some suspect such a strategy is also aimed at preserving the economy at the expense of older people, who are most at risk of dying from COVID-19, and whose premature death may even bring some additional short-term economic benefit to the state. Because of their poorer health systems, but also out of a culture of respect towards the elderly in the conservative societies of Central Europe, where intergenerational ties are strong, the post-communist countries of the Visegrád Four could not take that gamble, and this is also why they look to South Korea as a case-model, showing that this epidemic can be brought under control even in a democratic country, using a combination of fast reaction, social distancing, mass testing and people-tracking technologies.

Poland was in fact the second large European country after Italy to take serious social distancing measures at national level, closing its schools, universities, cinemas, museums, commercial centres and other venues from March 11, quickly followed by Slovakia which took the same kind of measures from March 12, and then Czechia from March 16 and Hungary from March 17. Slovakia was the first of the Visegrád Four to close its borders, and the other three V4 countries quickly followed suit, with Poland closing its borders to non-resident foreigners and imposing compulsory 14-day quarantine on all returning residents from March 15, Czechia doing so from March 16 and Hungary from March 17. In Poland, people in quarantine are subject to daily police checks and even electronic control through a smartphone application (since March 19). With return trips from abroad organised by the Polish government with the help of the national airline LOT, there were some 84,000 such people by Friday, March 27. Czechia had 22,000 people in quarantine by the same date. These figures are to be compared with the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases on March 27, respectively 1,244 in Poland and 2,062 in Czechia. In Czechia some kind of tracking similar to that applied in South Korea, using mobile phones and so-called “smart quarantine”, is expected to start from April, and the Slovakian parliament approved such measures on March 25. Of the above-mentioned Western European countries, only Italy has been working on ways to enforce such measures starting from March 23, but at the end of March both the V4 countries and Italy still fell short of general population tracking as in South Korea, where data from mobile phones, credit cards and monitoring cameras are used to trace all past movements and contacts of carriers of the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus in order to isolate those people and avoid the spread of COVID-19, while not having to resort to general lockdown measures of the kind which have been taken in Europe, in particular the more stringent ones which have now brought most economic activity to a halt in Italy, Spain and France.

The major difference between the V4 countries and their Western European counterparts lies in the timing of the measures taken (social distancing, border closure, controlled quarantine, ramping up of tests…). The V4 countries put those measures in place when the number of confirmed cases (in all four countries together) totalled between 103 (on March 11) and 726 (on March 17). When Italy closed its schools at national level on March 4, it already had 2,502 confirmed cases, and when it ordered its population to stay at home on March 10 it had 9,172 confirmed cases of COVID-19. France closed all schools on March 16 having 5,830 confirmed cases, and ordered a general lockdown on the following day with 6,573 confirmed cases. In the UK, under pressure from scientists and a quickly rising death toll, Boris Johnson retreated from his herd immunity strategy and ordered all pubs and all schools to be shut down from March 20, when the UK had 3,269 confirmed cases, while general lockdown measures came into force on March 24 when there were 6,650 confirmed COVID-19 cases. In Spain, social distancing measures were enforced at national level from March 13, with 2,965 cases already confirmed, and its borders were closed on March 16, when 7,753 people had been diagnosed as carrying the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

As a result, by the end of March, Italy, Spain, and France had also closed down most non-essential activities and the UK was about to take the same step, while in the V4 countries most companies were still running and were merely encouraged to resort to remote working wherever possible. Hence, by taking social distancing measures earlier, the Visegrád Four have been able – up to now – to keep their economies running. Borders remain open for goods, and the damage to international trade comes not from restrictions at borders but from the fact that many businesses have shut down for at least a few weeks in the above-mentioned Western European countries. (This does not apply to Germany, which has a different strategy, with social distancing measures but businesses still running as in the V4 countries, coupled with massive early testing; it also enjoys the benefit of having greater intensive therapy capacities than other countries and a much lower COVID-19 mortality rate, with 63,929 confirmed cases of the disease and 560 deaths by March 30.)

Another important factor in the fight against the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic is the level at which social distancing measures are broadly respected by the population. This is an important factor in South Korea’s success against the disease (just as in other East Asian countries such as Taiwan, Singapore and Hong Kong). A higher level of civic-mindedness in Central Europe than in Western Europe, and a higher level of resilience and collective thinking in societies where hard times are still not too remote in the collective memory, may also contribute to making a difference in the current crisis. In Lombardy, the worst-hit region of northern Italy, mobile phone operators’ data have shown that some 40% of people were not staying at home as asked by the authorities. Many inhabitants of the North moved to the South when Lombardy first ordered a general lockdown and was declared a “red zone”, before PM Giuseppe Conte took the same decision at national level. The same happened in Spain, when Madrid closed its schools and universities, and many inhabitants of the capital rushed to the seaside. In France, according to data from mobile phone operator Orange, as many as 1.2 million people, 17% of all inhabitants, left the Paris agglomeration between March 13 and 20. In France it is also reported that in many sensitive crime-ridden urban zones, where most inhabitants come from an immigrant background, the police are unable to enforce social distancing measures. No such problems have been reported since the beginning of the epidemic in the countries of the V4.

However, let us remember that the situation is extremely dynamic, and it will be for the future to show whether social behaviours and the earlier measures taken in Poland, Czechia, Slovakia and Hungary will really make a difference in the longer term in terms of the spread of the disease and its overall mortality.

——————

Sources of data for graphs:

- https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/

- https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports

Article originally published on Kurier.plus.