Interview with Ruuben Kaalep, member of the Estonian Parliament and member of EKRE, the Conservative People’s Party of Estonia: “We need to be able to play on the global stage, and for that we need to put our forces together and support each other. But the Intermarium has to be a voluntary alliance, not like the EU.”

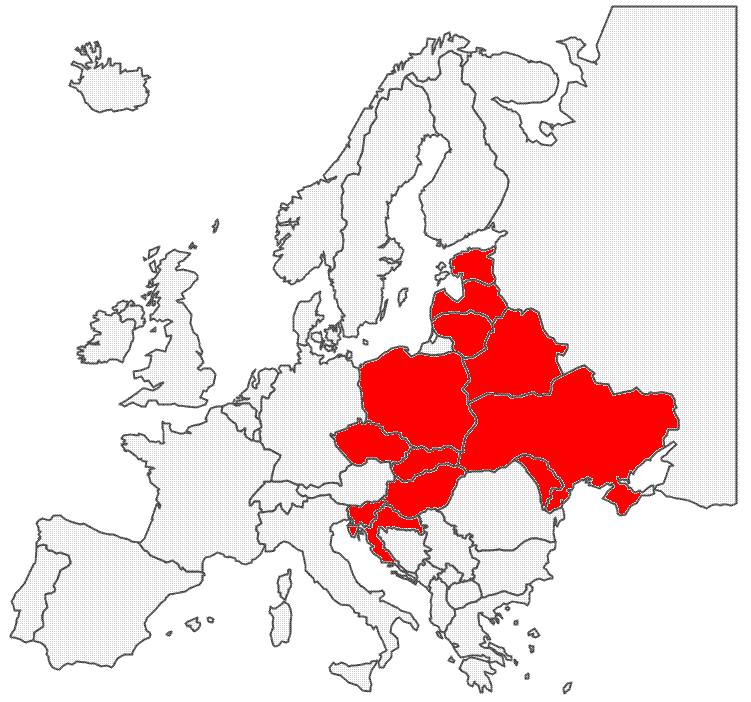

At the end of summer, Ruuben Kaalep came to Hungary at the invitation of the Hungarian nationalist party Mi Hazánk (Our Homeland). Ruuben Kaalep is one of the main advocates for the Intermarium project, a political and geostrategic plan aiming to regroup the Baltic countries, the Visegrád 4, Ukraine, Croatia, Slovenia, Belarus, Moldova, and Romania, forming a kind of a triangle between the Baltic Sea, the Black Sea, and the Adriatic Sea.

Although this list changes from time to time, sometimes including other Balkan countries, the Scandinavian countries, or even Austria, the Intermarium’s aim stays the same: to coordinate cooperation among the countries of Central and Eastern Europe — with the notable exception of Russia — in order to protect the interests of the region.

For its supporters, the project is the best way to preserve the way of life, security, and independence of the CEE countries, by “freeing them from Western domination and protecting them from Russian imperialism.”

The Intermarium project is not a new idea, although its revival gained visibility after the Maïdan revolution and the conflict between Ukraine and Russia, which the advocates of the Intermarium perceived as new Russian aggression necessitating regional cooperation to avoid such a thing in the future.

One hundred years ago, the post-WW1 reborn Polish state was dreaming of rebuilding the great Polish empire connecting the Baltic and the Black Seas, known as the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, able to contain Russia. This Międzymorze — “between-seas” — project of the Polish elites also included countries such as Hungary, Yugoslavia, Finland, Czechoslovakia, and Romania, making it the first modern project to bring together the CEE countries. Placed between Russia and the West, cutting off the Balkans from the rest of Europe, this geopolitical project always had many critics in both Russia and the West. Nowadays, if the Intermarium is mostly a little-known, pan-nationalist project, advocated mainly by Ukrainian, Balt, Croatian, and Polish political groups, the Three Seas Initiative can be seen as an implementation of Intermarium’s basic idea.

Intermarium has bigger ambitions than the announced goals of the Three Seas Initiative (gathering Baltic countries, the V4, Austria, Slovenia, Croatia, Romania, and Bulgaria) which is built on an energy and transportation cooperation scheme aiming to guarantee energy independence of the CEE countries from Russia while being financed by the USA. For the advocates of the Intermarium project, the future of the region should lie on the rejection of three main enemies: Russia, NATO, and communism.

Ferenc Almássy met with Ruuben Kaalep while he was in Hungary in order to discuss his advocacy of the Intermarium project.

Ferenc Almássy: You are member of the Estonian Parliament, but you are, can we say, a nationalist? Can you accept this epithet?

Ruuben Kaalep: Absolutely. A nationalist is what I am. It’s the main thing for me.

Ferenc Almássy: So how is it possible that in Estonia, nationalists are part of a governmental coalition?

Ruuben Kaalep: Right. Well, first of all, if you ask this from a Western European perspective, then things are very different right now between Western and Eastern Europe, ideologically different. Because what we see in Western Europe is that the people there, the dominant culture, has totally lost the sense of the sacredness of national and ethnic identity.

I think in some way, the division between Eastern and Western Europe is still being decided by our history; namely, the fact that our countries were dominated by Communist occupation for a long time and our national identity was forcibly suppressed. We have a strong counter-reaction to that. We feel that, in a way, the globalist Left-liberal ideology that is pushed upon us by the West is something very similar to Communism because it’s also totalitarian. It doesn’t accept other points of view that are outside the officially accepted paradigm. That’s one thing.

Now, how did it happen in Estonia that we firstly got to be a party with seats in Parliament, and then we entered the government? For a long time, there was a need in Estonian mainstream politics for something genuinely nationalist. There was a lack of it in the 1990s and after. And that was what I felt as a high school student who was interested in history, culture, nature, and so on. I was reading about Estonian history: the War of Independence, the Second World War, the freedom fighters, the Forest Brothers who fought long after the Second World War ended. They waged partisan war against the Communists. And I felt that something of that spirit was really lacking among the Estonian elite that was in power.

Ferenc Almássy: In the political representation?

Ruuben Kaalep: Yes, exactly. But the genuine nationalist groups at that time were small and divided. They fought against each other. They didn’t really have strong political perspectives until our party was founded in 2012. And it was founded out of the merger of a small but active nationalist group which I was previously a member of with an old, conservative agrarian party that had fallen out of the Parliament and which had lost all of its leaders. Its leaders had corruption scandals and things like that, and they escaped to other liberal parties. What was left was the structure of the party with many members who were totally normal Estonian people, mainly from the countryside, and they needed a clear ideology and clear leadership, which we nationalists provided. That’s how we built the party.

We started off right away as a strongly nationalist party. We stood up for all the things that were ignored by other parties. We raised the questions that no one dared to ask about the future of our Estonian ethnicity.

Ferenc Almássy: Like demographics, for example?

Ruuben Kaalep: Yes. Demographics, family values, all those sorts of things. That led us in 2015 to becoming a parliamentary party. Our success story continued in 2019 when we entered the Parliament with 19 members out of 101, making us the third-largest party in Estonia. This was because of the inner divide between liberals in Estonia. The two main parties in Estonia are liberal, but they have a long history of hating each other more than they care about liberal values. So we became a coalition partner with the Centre Party against another liberal party, the Reform Party, which is the main opposition party.

Ferenc Almássy: We are meeting in Hungary because you came to speak at a conference of the Hungarian nationalist party, Mi Hazánk, and you were debating with one of their MPs on the topic of Intermarium. Many people reading the Visegrád Post know about Intermarium. We are one of the few reporting on this. It’s strange, by the way, that it has received very little media coverage, but that’s another topic. In brief, this Intermarium project is usually either not known, or is seen in two different ways. One is a very optimistic vision of a fantasy Eastern Europe as the last stronghold of European culture. The other is that it’s seen as a tool of the United States to contain Russia. This is usually what you hear when people speak about Intermarium, at least in Western Europe, but also in Hungary. How would you answer both of these points of view?

Ruuben Kaalep: First of all, I wouldn’t say we were debating with Dóra Dúró [Mi Hazánk MP’s evoked in the question, ed.], because we agreed on pretty much everything. I absolutely think that Intermarium, or a geopolitical alliance between Central and Eastern European countries – the countries that have the weakest economies and a strong nationalist sentiment and sense of national identity – are already starting to understand what is happening in Western Europe, such as the migration situation, where they are allowing their own people to become minorities in their own countries. We understand that we can’t let this happen to our countries. So this is what unites us, and we need to cooperate, and we need to stick together, and we need to help each other, because that’s the only hope that the European people as a whole have right now. We are keeping the fire alive, while it is dead in the West.

Ferenc Almássy: So you would say that the primary aim of this cooperation will be to avoid the West’s liberal mistakes?

Ruuben Kaalep: Yes. And it would be absolutely different from the essence of the European Union in every sense, because the EU is built on different countries with very different values. They talk about European values, but what they consider European values is just a universalist, colonialist mindset from a globalist perspective. They don’t see the importance of rootedness in specific cultures or specific nationalities. We have that sense. It’s a very essential thing. That’s why we are able to see the danger to the whole of Europe and all European people, which is an existential danger. It’s the danger of extinction by being replaced by other cultures and other races, as is happening in Western Europe. We can only stop this and we can only save our countries if we do it together.

Ferenc Almássy: In what way, specifically? For example, the Visegrád Group is an informal group. There is no legal structure. It’s an ad hoc structure. What are you thinking of?

Ruuben Kaalep: I think we need to put those legal agreements in place, and we need to unite all of this. There are many forms of cooperation, diplomatic cooperation between these countries that—

Ferenc Almássy: That already exist.

Ruuben Kaalep: There’s already strong cooperation between the Baltic countries, there’s the Three Seas Initiative, different projects with Ukraine and Belarus—

Ferenc Almássy: The Slavkov Triangle and so on, yes.

Ruuben Kaalep: Yes. We need to unite them, but it has to be on a completely different foundation than the EU. It will not work if it’s forced down from above, from some power structure that tries to ignore the differences between various cultures and peoples. The idea of the EU is that they hope that these differences will just go away. This is a soft form of globalism. If you’re trying to turn Europe into one uniform part of this global supermarket, it doesn’t work.

Your previous question was about geopolitics. I think what is very clear by now is that the American influence on world politics is fading. It’s going away. They have so many domestic problems – racial conflicts, political conflicts. They will no longer be able to play this role of world police or of the global hegemon that they once had.

Ferenc Almássy: Also it is true that even if they were able to do so, they will probably not be able to do so at the same level, at least in Europe, since they are refocusing on the Pacific and China.

Ruuben Kaalep: Right. I think that in terms of geopolitics, the Intermarium countries have been dependent on American protection for decades. So there are risks. If American influence goes away, and we don’t stick together, if we’re not able to build our own strong geopolitical bloc, then we will become the playground of new empires like Russia or China who are only out for their own interests and don’t care about national values or ethnic nationalism, which is the main uniting ideological factor for our countries.

We need to be able to play on the global stage, and for that we need to put our forces together and support each other. But it has to be a voluntary alliance, not like the EU.

Ferenc Almássy: Just to get back to the second part of my previous question, some people criticize the idea of Intermarium as a satellite American project to contain Russia. What is your response to that?

Ruuben Kaalep: As I said earlier, America is no longer in a position to control what’s going on in the world, so there’s no point to these conspiracy theories which hold that everything is a tool of world government or something. If we put our forces together, that’s the only way for our countries to really stay independent, to focus on preserving our cultures and our countries. That’s the only way we can do it. If it’s a genuine cooperative project, it cannot be a tool or a puppet of any empire. We need to be able to stand up for our countries, and we can only do it together.

Ferenc Almássy: If you had to put the principles of this cooperation and the essence of this Intermarium project in only a few words, what would they be?

Ruuben Kaalep: It has to be based on the idea of national and ethnic self-determination. As a nationalist, I do believe that you can only respect other nations if you respect your own, and you can only respect your own nation if you respect others. There’s this old, stupid idea that nationalists of different countries are always supposed to hate each other. I think this is totally wrong.

Ferenc Almássy: When people speak about nationalism in this way, they’re actually speaking about chauvinism.

Ruuben Kaalep: Exactly. For almost a decade now, I have been meeting with nationalists from many different European countries. Every time, my experience in international nationalist meetings has been that I feel that this is the best chance for the true freedom of nations and the acceptance and cherishing of the true diversity that we have. This is what we stand for. What makes the world beautiful is the real diversity which comes from every nation having their own land. I think that’s the most important thing. This idea should be at the spiritual core of Intermarium.

Now in practical terms, I think that as long as the EU exists – I don’t think it will be a factor in the long run, because there are too many divisive issues within the EU that will cause it to collapse sooner or later – we need to always stand up for each other. When the globalists try to attack Hungary, for example, then we need all of the countries of Intermarium to unite and support Hungary. And it should be exactly like that for any other Intermarium countries.

What we also need – and I think in the longer term, it is crucial – we need military cooperation, because without that, we won’t be a strong geopolitical force.

Ferenc Almássy: You mean cooperation independent of NATO, or within NATO?

Ruuben Kaalep: Not all of the countries of Intermarium, such as Ukraine, are NATO members. So it will have to have a different format. Including Ukraine is crucial for Intermarium, because in geopolitics, in economics, and all of these factors, Ukraine is in a very decisive position.

Ferenc Almássy: You are one of the main advocates of Intermarium in the international scene. In which countries and among which political groups do you see the most support for and understanding of this project?

Ruuben Kaalep: I think the biggest proponents are the Baltic nationalists, who have a very good experience of cooperating with each other and who have no conflicts with each other, and who understand that we are facing the same threats. This is especially so with the Ukrainian nationalists, who are also very active proponents of Intermarium, because they have been very much left alone in their struggle against Russian occupation. I would like to see more support for that in the future from the Visegrád countries, because I think the Visegrád Group is the best example of that kind of cooperation that should eventually be expanded into a strong geopolitical bloc as Intermarium.

I’m optimistic about this. I see more and more people in this region understanding that we have a common past, but that we also have a common future, and we have common issues and common threats. So I think this is the most important thing.

Ferenc Almássy: In this Intermarium project, usually most of the Balkan countries are not included. Why do you not also see a common fate with them?

Ruuben Kaalep: I think the biggest problem that hinders the integration of Intermarium are all these old border conflicts between many of these countries, such as between Poland and Lithuania, Hungary and Romania, and so on. In the Balkans, it is much worse. Take the conflict between Serbians and Croatians, for example. There was a real war not so long ago, and I think it’s very hard to erase that memory. In those countries that I mentioned, we should never allow things to get that bad, because we shouldn’t forget that if we start fighting against each other, then we will lose all of Europe.

All of our countries are being threatened right now by the same problem, by the same threat from this globalist project that is erasing all national identities. To stop to that, we need to put our differences aside, even temporarily. We can only be successful if we can do that. Ideally, I would like to see all of the Balkan countries become part of Intermarium, but I think there needs to be some sort of reconciliation between them to make it possible. In practical terms, we have had talks mostly with the Croatians, who are really on the same page regarding the topic of Intermarium.