“The merchant should precede the soldier.”

Otto von Bismarck

“People will remain peaceful as long as

they believe they are rich and powerful enough to

insidiously put an economic dictatorship in place.”

George Bernanos

“Why should we remain the EU’s dupes?”

Viktor Orbán, May 2021

The Hungarian economic magazine “Új Egyenlőség”, in cooperation with the Friedrich Ebert Foundation, recently interviewed Andreas Nölke, professor in political science at the Goethe University in Frankfurt and author of a number of comparative works concerning capitalism. In 2018, he published an article analysing the different paths taken by the emerging markets with regards to dependent capitalism and state-permeated capitalism.

According to Nölke, the V4 countries are the perfect examples of dependent market economies. Let’s critically summarise his approach and to compare it with other examples:

Nölke considers market economies as being dependent when they have a high proportion of foreign direct investment (FDI) as part of their GDP. This proportion forms a consistent pattern since the start of European integration. This method of measuring economic dependency shows that, with regards to emerging markets, there are no other economies (a possible exemption being Northern Mexico) are as dependent on FDI as those of the V4 countries and, broadly speaking, Central and Eastern Europe. Indeed, other emerging economies, as well as those of so-called developed countries, rarely does FDI represent more than 1/3 of their GDP.

The Visegrád Group – Thirty years of economic dependence?

In thirty years, this region of Europe has become somewhat of a “heaven for multinationals”, a place where salaries are relatively low, people are sufficiently trained/qualified, weak banking regulations and a near-perfect openness when it comes to foreign investments. It is this path of economic openness and Western integration that the Central European countries decided to tread since the beginning of the 1990s and have never veered off it.

Even though national economic elites (notably those of Hungary since 2010) occasionally manage to get their hands on a certain number of secondary sectors,

the potential high growth sectors are controlled by foreign investors, in such quantities that it will be impossible for anyone in the region to achieve national economic independence.

If economic sovereignty is all but absent in the region, Nölke notes that the growth and employment rate are satisfactory when compared with those of other countries in the EU but also questions the sustainability of this form of dependent market economy beyond a period of 5 to 10 years.

For example, whilst German industry has very recently stated how satisfied it was with the state of the Hungarian market and since no German political force seems to want to call into question German economic fundamentals, which is export-orientated economy,

the dependent market economies are by nature unstable since they are tributaries of economic and political decisions that are outside the grasp of Central European governments.

Another example amongst others is that if Germany came to decision to give more importance to domestic demand (which could mechanically happen, depending most notably on what China decides to do since half of Germany’s exports go to that country), then it is the V4 countries that will immediately come out losers.

Since the countries of Central Europe do not have direct control of a big part of their national wealth production, their economic models are inevitably quite fragile. The local authorities of these countries are perfectly aware of this vulnerability, hence why they have endeavoured to not only maintain favourable conditions for foreign investments but also to actively support foreign companies based within the region. The latter opportunistically take advantage of dependent situation that these countries find themselves in. This is what Hungary notably did March 2020 and what it had done in 2010 by providing very generous hand-outs to the multinational companies.

This model is the complete opposite to the one adopted by other emerging countries (with much larger markets, such as China) that have chosen to protect their national businesses from foreign investment. Within these countries, the amount of FDI with the GDP is much lower than in the ex-Communist countries of Europe and their governments have a role in protecting key economic sectors and are quite concerned to not let foreign investments take control of potential high growth parts of their markets.

Whilst the countries of Central Europe’s dependence on FDI have opened their doors in mid- or long-term instabilities, it has also permitted much bigger issues to appear, notably as

a way of oppressing the economic and social development of these countries, which are kept afloat with cash injections in key sectors, but just enough in order to keep control of these countries and never enough to kick-start any sort of progress (such a semi-automated production for example).

Whilst acknowledging that these good growth rates, built upon foreign investments, do not follow down throughout society than the weaker rates of lesser dependent economies,

the evidence is ghastly. On the very long term (since 1870), the GDP gap per inhabitant of the modern V4 countries and a selection of 12 Western European countries has never stopped growing and has accelerated since 1990.

Furthermore, one should keep in mind that these injections of foreign capital do have a down side, which is that they eat away larger and larger chunks of these countries’ wealth. In other words, the amount of profit that is sucked out of these countries is more than the amount being invested and, on top of that, there is an exodus of people from these countries for economic reasons. Both these factors can be trivially summarised thus by saying that

the Central European economic model helps finance German pensioners, who are taken care of by staff trained in peripheral countries.

As we know, this state of dependency has not been imposed by military might (even if some talk about the cost to pay to benefit from the American nuclear umbrella) even though Nölke does mention this as being an option.

Is it only economic and political dependency?

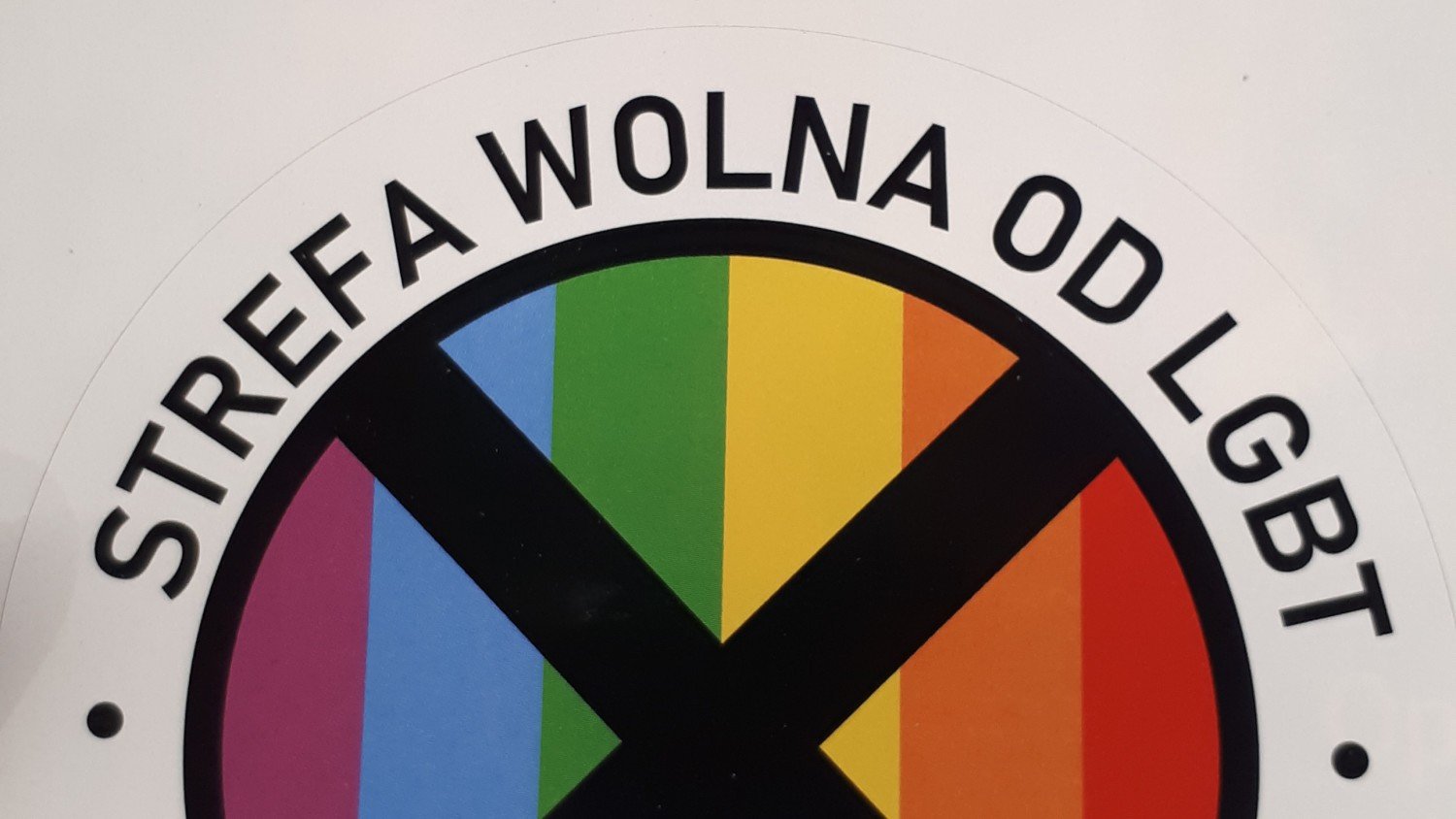

This state of economic dependency naturally extends into politics which, in Central Europe, cannot be truly self-determining unless authorised by Western creditors. Whilst certain regional nations, notably Hungary and Poland, have managed to find more of a voice in the last few years, it is essentially to speak about “civilisational” subjects such as immigration and LGBT rights. In other words, on subjects that will not disturb the current economic status quo described previously.

The countries of Central and Eastern Europe didn’t have any other choice than to go down this path of economic dependency at the conclusion of the Cold War. Yet it would be incorrect to say that this path was imposed by force. In reality, the local elites, as well as the vast majority of their citizens, were overwhelmingly in favour of this economic paradigm.

Again, although the people are not as enthusiastic as they were at the start of the 1990s, there is nothing to indicate that, after thirty years, any significant group wishes to change this economic and political status quo.

It should be noted that Hungary, for example, there does exist a will to diversity inward investment by reaching out to Asian partners. This openness to the East doesn’t call into question the status quo but rather marginally changes its nature.

On the whole, can we say that these countries are genuinely committed to this state of dependency? Let’s take the case of Hungary: Whether they be in office or in the opposition, there doesn’t exist, to the best of our knowledge, any political force with ambitions to call into question this status quo. Quite the contrary, despite both sides of the political aisle eagerly clashing in rhetorical battle, the opposition (which is completely pro-EU and Europeanistic) and the government hardly differ on the state of dependency of their country and neither wish to put an end to it.

The Hungarian opposition does not hide its direct and unconditional commitment to the different Western institutions. The government’s links to this Western dependency is more complex.

The Hungarian government doesn’t hesitate to criticise its Western partners. It does this in order to play catch-up and wanting to prove its country is capable of fairing better than those of Western Europe. Everything that technically started the COVID era in March 2020 has proven that perfectly. Indeed, by wanting to be a trail-blazer, the Hungarian government took the lead when talking about the new economic landscape, health passports and mass vaccination campaigns. This lead was praised by the World Health Organisation and the newspapers “Die Welt” and “New York Times”.

This isn’t a critic towards the state of dependency but rather a quest for recognition which doesn’t call into question the current economic, political or mental status quo as described before.

Finally, the recent controversy, instigated by government media, concerning the poor level of English by Gergely Karácsony (mayor of Budapest and opposition candidate for the position of Prime Minister) reveals to all this dominance of this state of dependency: The opposition does not need to demonstrate its allegiance to the West whilst the government is also desperate to show to everyone how “modern” and “European” it can be too in order to woe the intellectual elites of Budapest, who are overwhelmingly internationalists.

After all this, the conclusion is scathing: Yes, economic and political dependence exists but it is an accepted dependence, perhaps even a wanted dependence. Although some will probably not understand why anyone would want to be dependent, we know that real dependence is not being addicted to an object but rather that true dependence is getting someone hooked on sufferings that their addiction generates.