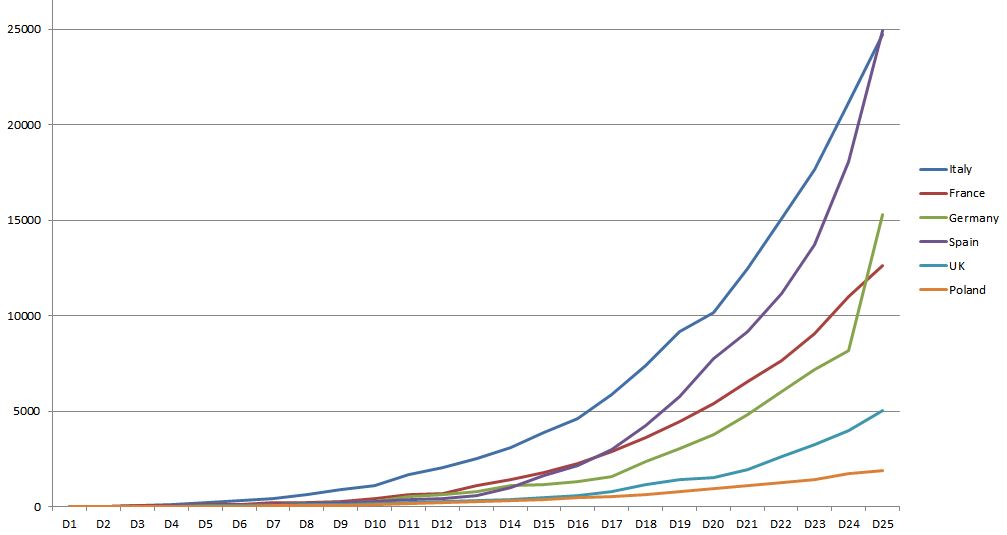

Poland – Almost four weeks after the first case of COVID-19 was detected in Poland (a Polish national returning from Germany who was tested positive on March 4), the measures taken by the government seem to have had a positive impact, like those taken in the other countries of the Visegrád Group. In contrast to countries in Western Europe, where the spread of SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus has been exponential in its first phase, up to now Poland, a nation of 38 million people, has recorded a linear progression of the epidemic:

D1 = date from which new cases of COVID-19 have been confirmed every day: February 21 for Italy, February 25 for Germany, February 26 for France and Spain, February 27 for the UK, March 6 for Poland

(data sources: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/ and https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports)

As of March 30, Poland had 1905 confirmed cases and 26 deaths related to the SARS coronavirus, with 46,607 tests having been carried out since the beginning of the month. Warsaw’s strategy has been to respond right from the beginning of the outbreak on national territory, ordering from Thursday, March 11 (before France, the UK or Spain) the closure of schools, universities, cinemas, theaters, museums and shopping centers, and prohibiting public gatherings of more than 50 people, including in churches on Sundays, which the Polish Episcopate was able to comply with by increasing the number of masses while giving the faithful a dispensation from the obligation to attend Sunday mass. Since March 11 restaurants and bars have only been allowed to serve takeaway dishes and drinks or to offer home deliveries. Poles were asked to keep a minimum distance of 1.5 meters between them, and stores began to obtain protective equipment for their staff. There were fewer than 30 known cases of COVID-19 in Poland when those measures entered into force.

The closure of borders has been the second axis of the Polish containment strategy against the epidemic, and Poland was one of the first European countries to take this kind of measure, ignoring protests from the European Commission. Since March 15, only Polish nationals and foreigners with residence permits have been allowed to come to Poland. The closure of the border to non-resident foreigners does not, however, affect the transport of goods. At first, truck drivers had to go through stringent health controls, but the Polish authorities later had to exempt them from these because of the huge traffic jams this caused, with shortages of some imported products in stores as a result. But all Polish and resident foreigners returning to Poland must go through a compulsory 14-day quarantine in their homes, with daily police checks and localization control through a smartphone application. In case someone violates the very strict conditions of their quarantine, which exclude all contacts with other people (even their groceries must be left on their doorstep by someone else), that person is liable to a fine of 30,000 zlotys and up to one year in jail.

With the assistance of the LOT national carrier, the government of Mateusz Morawiecki has organized charter flights to repatriate Polish people who found themselves stuck abroad after the closure of regular air routes from March 15.

At the end of March, more than one hundred thousand people were in quarantine in Poland.

Furthermore, the government decreed a generalized confinement of the population starting March 25. People are permitted to go out only when really necessary (but without any need for a written justification), such as when going to work (most companies continue to function even thoughremote working is mandatory whenever it is possible), doing their shopping (most stores remain open outside malls,where only supermarkets are still permitted to open), or even going out for a walk, on condition they do not gather in groups of more than two persons from different households. All gatherings, including religious ones, are now limited to five people, and this new rule has in fact suspended Sunday masses, which Polish Catholics must now follow on television or on the Internet. Such prohibition of worship may come as a surprise in this Catholic country, while, for example, the maximum number of people allowed on city buses is limited to half the number of seats.

In an interview published in the Do Rzeczy weekly on March 16, minister of health Łukasz Szumowski explained why social distancing measures should be enforced at the very beginning of an epidemic: “Once the virus is already circulating in the population, such measures have less sense. Today, if several million people stop taking buses and cease to meet at schools and universities, it gives us a chance to limit the spread of the virus.” The health minister, who is a cardiologist, has become something ofthe hero of the hour in Poland, with his daily press conferences, his eyes ringed with fatigue, and his quiet, factual style. Professor Szumowski was one of the signatories of the Polish declaration of faith of Catholic doctors in 2014. Today he is in third position in the ranking of political personalities whom Poles trust the most, just behind President Andrzej Duda and Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki.