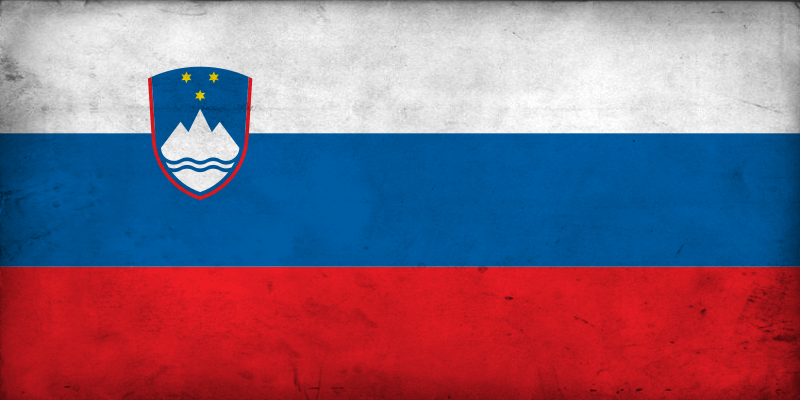

European Union – The interior ministers of the 27 European Union member states met in Brussels on December 8 to decide on adding three additional countries to the bloc’s Schengen Zone: Croatia, Romania, and Bulgaria. Bulgaria and Romania had joined the EU together in 2007, and their demands to join Schengen have been continuously rejected since 2011. This relates to avery important detail: Romania and Bulgaria’s demand to join the Zone is a joint application, which means that their accession to Schengen can only be accepted or rejected together rather than separately. Croatia, for its part, joined the EU in 2013 and has been applying for Schengen since 2015.

In the end, the 27 ministers voted unanimously, as EU law requires, in favor of admitting Croatia to the Schengen Zone. As a result, Croatia will join both the Eurozone and Schengen on January 1, 2023.

Romania and Bulgaria were rejected, however, as the Netherlands and Austria opposed their acceptance. While the Netherlands’ opposition to their admission is nothing new, Austria’s dissension is a recent development.

But the most interesting part of the story is the incredible hypocrisy of the arguments given in order to justify Romania and Bulgaria’s rejection.

Migration issues were Austria’s motivation for vetoing the accession of the two Balkan states. This accusation is quite ridiculous, however, since Austria did not oppose Croatia’s admission, despite the fact that it shares a 932-kilometre border with Bosnia which is not easy to properly control, as well as a 217-kilometre border with Serbia. Since the beginning of the migrant crisis in 2014, Romania and Bulgaria were in fact precisely among those few Balkan countries which did not have big migration problems.

As a consequence of Austria’s refusal, anger flared in Romania. Euractiv reports that a certain number of Romanian entrepreneurs mentioned the possibility of boycotting the Austrian-owned banks BCR and Raiffeisen, as well as the country’s oil company, OMV.

I can also add a related personal anecdote: in recent weeks, people I know told me about the incredible difficulties they had in crossing the border between Moldova and Romania, given that since the autumn Romania has significantly reinforced its control measures via the addition of many EU border guards who were present to verify whether Romania is able to properly secure them. Interestingly, I’ve likewise been informed that my colleagues there did not see any Hungarians among these foreign border guards; I have no solid evidence concerning the reason why, but I can easily assume that since the Hungarian government is in favour of Romania joining Schengen, in part to ease the ability of the Transylvanian Hungarians to enter Hungary, they didn’t want to needlessly harass the Romanian authorities by sending additional guards there.

But given that there are nevertheless still tens of thousands of migrants in Serbia who are aggressively trying to enter Hungary almost every day, it will be interesting to see if Croatia’s membership in Schengen will encourage these migrants to try to enter Schengen through Croatia instead of Hungary.

When it comes to the Netherlands, we’re talking about a country which has always been enemy number one of Romania joining Schengen. Despite the fact that it is rarely mentioned outside of the Romanian media, the main reason for this is that were Romania to join Schengen, the Port of Constanța would begin seriously competing with the Port of Rotterdam, which is currently the largest seaport in Europe.

For individuals, Schengen means the ability to cross national borders without having to lose time in dealing with border controls. Those who have crossed from Hungary to Transylvania or Austria – since Austria has again been controlling its border with Hungary in recent years – knows it can take either a few minutes or, in unlucky circumstances, several hours.

But the real issue in this case is trucks. When trucks enter the Schengen Zone, including when they are crossing from Romania into Hungary, they have to wait for several hours or even days. Whoever has crossed the Romanian-Hungarian border by land, especially at Nagylak, has witnessed kilometres-long lorry queues along the roadside. These delays have significant consequences in terms of delays and the cost of transportation. Bringing Romania into Schengen will end these delays and make the Port of Constanța attractive for cargo ships coming to Europe from Asia and through the Suez Canal, since their voyage might be significantly shortened by docking at Constanța instead of Rotterdam.

Romania’s efforts to convince the Netherlands to end its blocking of the country’s accession to Schengen went quite far, since they even purchased two firefighting vessels at a cost of 44 million euros from a Dutch company in October prior to Dutch PM Mark Rutte’s visit to Romania.

But in a very cynical tactic, the Netherlands’ government declared itself as still being opposed to Bulgaria’s accession to Schengen while favouring Romania’s – despite the fact that it de facto means Romania will be denied as well, since Romania and Bulgaria’s demands are made jointly.

To explain his country’s opposition to Bulgaria’s admission, Rutte referred to human rights and corruption issues as well as migration problems, declaring that it’s possible to enter Bulgaria from Turkey with a 50-euro note. This last remark was not well-received, especially given that in November a Bulgarian border guard was shot to death by a migrant.

Romanian Professor Sergiu Mișcoiu of Babeș-Bolyai University warned that this latest rejection of Romania and Bulgaria might strengthen Eurosceptical political forces, “especially in Bulgaria, where there’s already been four elections in the last two years.”

George Soros’ Open Society Foundations also recently revealed that support for Schengen among Bulgarians is decreasing.

In the days following the vetoing of Romania, demonstrations and calls for boycotting Austrian companies such as OMV and Red Bull were organized all over Romania. Unsurprisingly, the populist Alliance for the Union of Romanians party was on the frontlines of this topic.

In conclusion, the most interesting aspect of the story might be this: despite the strong desire of the globalist elites to irreversibly deepen “European integration” as much as possible, along with its institutional pillars (the EU, NATO, the Euro, and Schengen), there are still some disagreements and/or inconsistencies (or simply vanity?) over the implementation of this policy.

Only the future will show if the Eurosceptical forces will be able to exploit these weaknesses.