By the editorial board.

What will the European Parliament look like after the elections of May 26? Chess game in Central Europe, Salvini’s activism, repositioning of Western European populists, consequences of Brexit and questions about Fidesz and ANO.

After meeting with Viktor Orbán in Italy in August 2018, Matteo Salvini visited Poland in Warsaw on January 9, 2019, where he met with the leader of Poland’s ruling party Law and Justice (PiS) Jarosław Kaczyński. He said that Italy and Poland would be “the protagonists of this new European spring”. Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán described the alliance between Italy and Poland as “one of the greatest developments that this year could have started with”. Other columnists mention Salvini in the opposite opposite way, as someone who is “flying blind up” in his search for political alliances at the European level.

While Matteo Salvini met the PiS leaders, Luigi Di Maio – the figure of the other partner of the Italian government coalition, the Five Star Movement – met with Polish populist leader Paweł Kukiz to conclude an agreement for the next European elections. Shortly after that, Mr. Di Maio expressed his interest in associating with a possible political emanation of Yellow Vests in France.

These meetings are an opportunity to sort out these games of European alliance four months ahead of the European elections.

High-stakes elections?

If there is one subject on which almost all sides of the political spectrum in Europe seem to agree, it is importance of the European elections of May 2019. With a clash between two represented tendencies (at least symbolically), one by French President Emmanuel Macron, the other by Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán.

Macron and Orbán did not fail to identify themselves as representatives of opposing camps: during his visit to Bratislava Macron described the Hungarian and Polish rulers as “crazy minds” who “lie to their people”, while Orbán called Macron the leader of a “pro-migration camp” during his travel to Italy to meet Interior Minister Matteo Salvini in August.

In September 2018, when Orbán had come to Strasbourg in person to speak about the Sargentini report against Hungary, he once again spoke about the time horizon of May 2019: “We Hungarians stand ready for the elections next May, when the people will finally have the chance to decide the future of Europe, and will have the opportunity to restore democracy to European politics“.

Even if the European Parliament is not the only governing body of the European Union and it is unlikely that the elections in May 2019 will lead to a radical change in the EU, its symbolic importance (as it is the only democratic instance of the EU) and its role in the institutions (notably at the beginning of their term, for the investiture of the European Commissioners) are not to be overlooked.

In January 2019 Viktor Orbán reaffirmed his ambition that a majority, hostile to immigration, would emerge in every institution of the European Union. The first step is the European Parliament, then the European Commission and finally the European Council, as the national parliamentary elections would bring to power governments hostile to mass immigration.

The current balance of power and the foreseeable consequences of Brexit

Since the establishment of a European Parliament elected by universal suffrage in 1979, the two majority groups in Parliament are the EPP (European People’s Party, Christian Democrats) and the Social Democrats, and usually they have a habit of constituting together a majority that shares the Presidency of Parliament at regular intervals.

In January 2019, the distribution of 750 seats is thus established:

– EPP: 218 deputies (including those of Hungarian Fidesz)

– Social-Democrats: 186 (including the elected representatives of the Slovak SMER and the Romanian PSD)

– ECR (European Conservatives and Reformists): 74 (including 19 Polish deputies, among them the members of PiS, and 19 British Conservatives)

– ALDE (Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe, led by Guy Verhofstadt): 68 (including the 4 elected officials from the Czech ANO party)

– Greens / EFA: 52

– GUE/NGL (European United Left-Nordic Green Left): 52

– EFDD (Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy): 43 (including 19 UKIP members and 14 Italian Five Star Movement members)

– ENF (Europe of Nations and Freedom): 34 (including 15 French NR members, 4 from the Austrian FPÖ, 6 from the Italian Lega Nord)

– non-attached: 23

This current balance of power gives an absolute majority (of 375 seats) to the EPP and the Social Democrats, that together constitute 404 of the 750 seats. One can also count the liberal deputies of the ALDE among the solid parts of the “pro-Brussels” majority.

More to the left, the Greens and GUE groups are globally pro-European and pro-immigration, some of the nuances or disagreements with the majority tendencies are related to environmental issues, economic free-trade (TTIP, CETA), even with the issue of EU-Russia relations with regard to the GUE/NGL group.

On the right of the EPP, there are 3 parliamentary groups:

– the ECR group, which managed to be the third political force of the parliament in 2014, notably by rallying the Flemish N-VA; this group brings together conservatives and other Christian Democrats who are at odds with the EPP, and even some right-wing populists; however, they keep distance from elected officials who could be qualified as far right, including the exclusion of the German AfD MEPs in March 2016

– the EFDD group, of which the two main pillars are the British UKIP of Nigel Farage and the Italian Five Star Movement; at the beginning of 2017, the attempt of departure of Five Star Italian politicians to the liberal ALDE group culminated in failure with the ALDE group’s refusal to accept them; in addition to its two heavyweights, the EFDD group includes several French deputies who left the RN (formerly FN), a Polish deputy who came back during the mandate to maintain the group, and the former Lithuanian president Rolandas Paksas

– the ENF group, which was not able to come into being in 2014 because of the difficulty of bringing together parliamentarians from 7 countries, and was constituted during the term of office, thanks to the rallying of a former British UKIP representative and of two Polish politicians of KPN which have become possible to integrate after the ousting of their former leader Janusz Korwin-Mikke

A new caryall EFDD group with the Five Star Movement?

Brexit will dramatically change the situation for the groups to the right of the EPP. The future of the EFDD group is the most concerned with the departure of the British and the positioning instability of the Five Star Movement.

Until now, the EFDD group (which was called EFD during the 2009-2014 term) was essentially Nigel Farage’s instrument used as a platform to promote Brexit. As group chairman, Nigel Farage was able to perform lengthy interventions in the front row of Parliament, which he used to make himself famous in the UK and beyond.

Apart from the UKIP and 5 stars, the EFDD group consists essentially of allies of circumstance without a necessarily very strong ideological coherence. Thus, this group was formed in 2014 by winning over a French FN deputy in break with her party or the Swedish Democrats – initially allied with the French FN but finally choosing to associate with Farage, seen as showing less radical views. One should also note that this group almost disapeared following the departure of a Latvian MP and won over within 48 hours a Polish MP (Robert Iwaszkiewicz) from the lists of Janusz Korwin-Mikke, a strong personnality that many do not want to be associated with. This is an evidence of the flexible nature of Farage’s strategy, serving a single purpose: to provide a forum for promoting his political message.

It would seem, then, that Farage’s main desire was not to be in the same group with Marine Le Pen, both for image reasons and not having to cohabit with another strong personality in the same group.

The Italian Five Star Movement seems eager to retain the EFDD group that it was trying to leave in 2017. Due to its political weight, the Five Star Movement would inevitably take the leadership of this group.

Several allies have already been found to achieve this goal: in addition to the Polish Kukiz movement, the Five Star Movement claims to have reached agreements with the Croatian party Živi zid described as populist and the Finnish liberal party Liike Nyt.

As in the 2014-2019 term, the eventual future of the EFDD group led by the Five Star Movement will grant full voting freedom to its members, which should favor its ability to recruit free electrons to bring together the 7 nationalities needed for the constitution of a group.

The ENF group will also have to struggle for its survival

The ENF group currently has 8 nationalities. If it remained as it was, it would just have the required 7 nationalities after the withdrawal of the United Kingdom. But it is not certain that all its members will be re-elected (including the Polish politicians of the KNP) or remaining in the ENF group (the positioning of the Salvini’s Lega is for the moment uncertain). Other allies could however come in reinforcement, with for example the possible entry into the European Parliament of the Czech nationalist SPD party led by Tomio Okamura.

It is not impossible that the group does not manage to reconstitute itself because of the constraint of the number of nationalities to gather (the contingent of elected representatives of the French RN is almost enough alone to obtain the 25 elected necessary). Everything will depend on how parties such as the Italian Lega or the Austrian FPÖ are going to position themselves: they have become during the 2014-2019 term governmental parties, which could make them more acceptable to potential partners who are essentially in the ECR group.

However, it is also unsure that the heavyweights of the ECR group have an interest in the fact that heavyweights like the French RN (which can hope to send another twenty MEPs to the European Parliament in May 2019) are totally left behind after the elections and find themselves without a parliamentary group, due to the unfailing support of these MEPs to the Polish or Hungarian governments when they have been attacked – vote on the basis of the article 7 – in the European Parliament in recent years.

The future of the ECR Group and the unlikely Eurosceptic common group

As for the ECR group, if it is not threatened with extinction consequently to the departure of the British Conservatives, it will nevertheless be weakened by the departure of the 19 British MEPs. In order to maintain its position as the third political force in the European Parliament, the ECR group will therefore have to expand to new partners, especially as the ALDE group could be reinforced by the elected representatives of the French presidential party LREM which did not existed back in 2014.

The ECR group could be reinforced with the Debout la France party of Nicolas Dupont-Aignan, currently unrepresented in the European Parliament and previously associated with the EFDD of Nigel Farage, as the French politician has just concluded an agreement with the ECR group. Of course, that is only if the votes in May 2019 would grant with at least 5% of the vote the list that will lead Nicolas Dupont-Aignan; but this is what the polls suggest currently.

Jan Zahradil, Czech MEP and “Spitzenkandidat” of the ECR Group for the European Commission, also mentioned the Italian Lega as potential new partner of the ECR group. But he seems to discard cooperation with the French National Rally (former FN) or the German AfD, evoking in particular geopolitical differences of opinion between the partisans of Atlanticism and the Russophile parties.

If the question of Russia is partly relevant, especially for Poland, it cannot be the only argument, especially if one takes into account that the Russophile position of Matteo Salvini did not prevent him from being received in Warsaw. In reality, the Hungarian and Polish rulers seem to allow themselves to organize official meetings with leaders of political parties in Western Europe which are qualified as populists or eurosceptics as far as they are part of the ruling coalition government, and such a meeting can be presented as inter-governmental. That was the case for the meetings held between Viktor Orbán and the Austrian Vice Chancellor Strache (leader of the FPÖ) or Italian Interior Minister Salvini, and now it is the same for the meeting between Kaczyński and Salvini.

Conversely, although they remain loyal to their French partner of the RN (ex-NF) with which they sit in the European Parliament within the ENF group until the end of the 2014-2019 term, the leaders of the Italian Lega and the Austrian FPÖ have shown in recent months more interest in appearing with Orbán or Kaczyński. As evidence, one can consider the absence of great figures like Salvini (who sent a video message) or Strache (represented by Harald Vilimsky) at a European meeting organized by the RN in Nice on May 1, 2018.

Does this mean that the Lega joining of the ECR group after the 2019 elections is on track? In any case, the German Manfred Weber, appointed by the EPP to compete to the succession of Jean-Claude Juncker at the head of the European Commission, made it clear: he would look favorably on the Lega’s joining of the ECR, implying the abandonment of the ENF group with the RN party of Marine Le Pen.

And it seems that Salvini, behind a seeming dispersal attitude, wants actually to keep all doors open, since he maintains good relations with Marine Le Pen, that he welcomed in Italy in October to announce a “Freedom front” in view of the 2019 European elections.

Some voices, including those of Salvini or the German AfD, have expressed their wish to see the emergence of a common Eurosceptic group after 2019, that would bring together the forces that can currently be found scattered among the groups ECR, EFDD and ENF. Such a group could exceed one hundred of MEPs.

The possibility of such a group is, however, low, particularly because of the impact it could have on some of these government-level parties at the national level to associate with certain formations considered too marginalized or marginalising.

Whether the prospect for the PiS to be in the same parliamentary group as the RN or Vlaams Belang does not seem to be on the agenda, Olivier Bault notes, however, that “an evolution is being felt within the PiS regarding the attitude towards the French national movement and Marine Le Pen“.

Indeed, when the European Parliament votes against the Polish or Hungarian governments, both of the Central European countries have always been able to count on the support of the elected representatives of the ENF group, and they are seeking – without necessarily associating themselves politically with them – to maintain the cordiality in relations with these political parties.

We can therefore imagine two groups (if the ENF group is able to reconstitute itself) on the right of the EPP after 2019, with informal coordination between these groups, especially since most Euro-Critical parties have generally given up their desire to exit the EU or the common currency.

Questions about Hungarian Fidesz and Czech ANO

The continued presence of Fidesz within the EPP has been the subject of many debates and speculations for several months. Jean-Claude Juncker himself said that he believes Fidesz no longer has a place in the EPP, while Manfred Weber voted the Sargentini report against the Hungarian government.

The question is sometimes raised even in Hungary, like it was made publicly at the 2018 Summer University in Tusványos, where Viktor Orbán gives a speech of general political analysis every year.

However, Fidesz is not totally isolated within the EPP and still enjoys strong support, such as that of its president Joseph Daul. During the vote on the Sargentini report, Fidesz could still rely on several reliable allies, such as Forza Italia’s elected representatives, ot the ones of Croatian HDZ or Slovenian SDS.

As for Viktor Orbán, his communication on the subject is inflexible: there is no question for him to see Fidesz leave the EPP.

As for the EPP, despite the embarrassment of part of its ranks to keep Fidesz in its midst, the challenge is also to remain the majority group in the European Parliament. Despite Hungary’s low demographic weight in the EU, Fidesz’s electoral results mean that the Hungarian delegation of the EPP is, in numerical terms, the fifth one of the EPP.

However, the hypothesis of exclusion of Fidesz would imply the departure of a dozen of MEPs (presumably towards ECR, which does not fail to say that it would be welcoming them) or other partners. That hypothesis would be damaging for the EPP, but also for Orbán’s strategy that seems to be to bring its partners on its line rather than to be marginalized on the European scene.

It should also be noted that the strong influence of Fidesz on Hungarian minority deputies in Romania (from the RMDSZ-UDMR party) or even Slovakia (if one of the two Hungarian parties, the MKP, close to Fidesz, manages to maintain its representation in Parliament) Fidesz actually has a potential influence on fifteen Hungarian MEPs (12 of Fidesz, 2 of UDMR and the one of MKP).

If Fidesz finds itself excluded and manages to bring with it its Hungarian minority allies, as well as other Italian, Croatian or Slovenian partners, then the EPP could have a smaller number of deputies than the social-democratic group (as far as it is likely that the German CDU or the French LR will have lower electoral results than in 2014).

In any case, it seems there will be no move from Fidesz or the EPP before the European election and the following steps (notably on the appointment of European Commissioners).

The other question, which is more well-founded, is where the MEPs of the Czech government party ANO of Prime Minister Andrej Babiš will sit. Indeed, they currently sit in the ALDE group led by Guy Verhofstadt. They voted in favor of the Sargentini report against the Hungarian government, which provoked the anger of Andrej Babiš, who distinctly disassociated himself from the ANO MEPs’ vote, stating that they would no longer be elected in a year, feeling sorry for their vote but stating that their vote is their own decision.

It is hard to imagine that the new members of the ANO will sit again in the ALDE group during the next term of office. Due to the hostile positioning of their leader on migrant quotas and his solidarity with Orbán, one can imagine as an option that the new members of the ANO sit within the ECR group.

What about the left-wing populists of Central and Eastern Europe?

On the left, the presence in the group of Social Democrats of the Slovak SMER (the majority party of the government coalition) and the Romanian PSD sometimes raises questions, because of the “populist” orientation of the exercise of power of these two formations. In the past, the SMER has been heavily criticized for the past government alliances with nationalist right parties (notably the SNS) in Slovakia.

Talking about the global situation in Europe, the presidential candidate for the European Commission Manfred Weber doesn’t forget the Romanian Socialists of the PSD: “If I look at the European political landscape today I see Salvini in Italy, Kaczynski in Poland, the Romanian socialists, Orban. We could wish for something else, of course. But that’s the reality“.

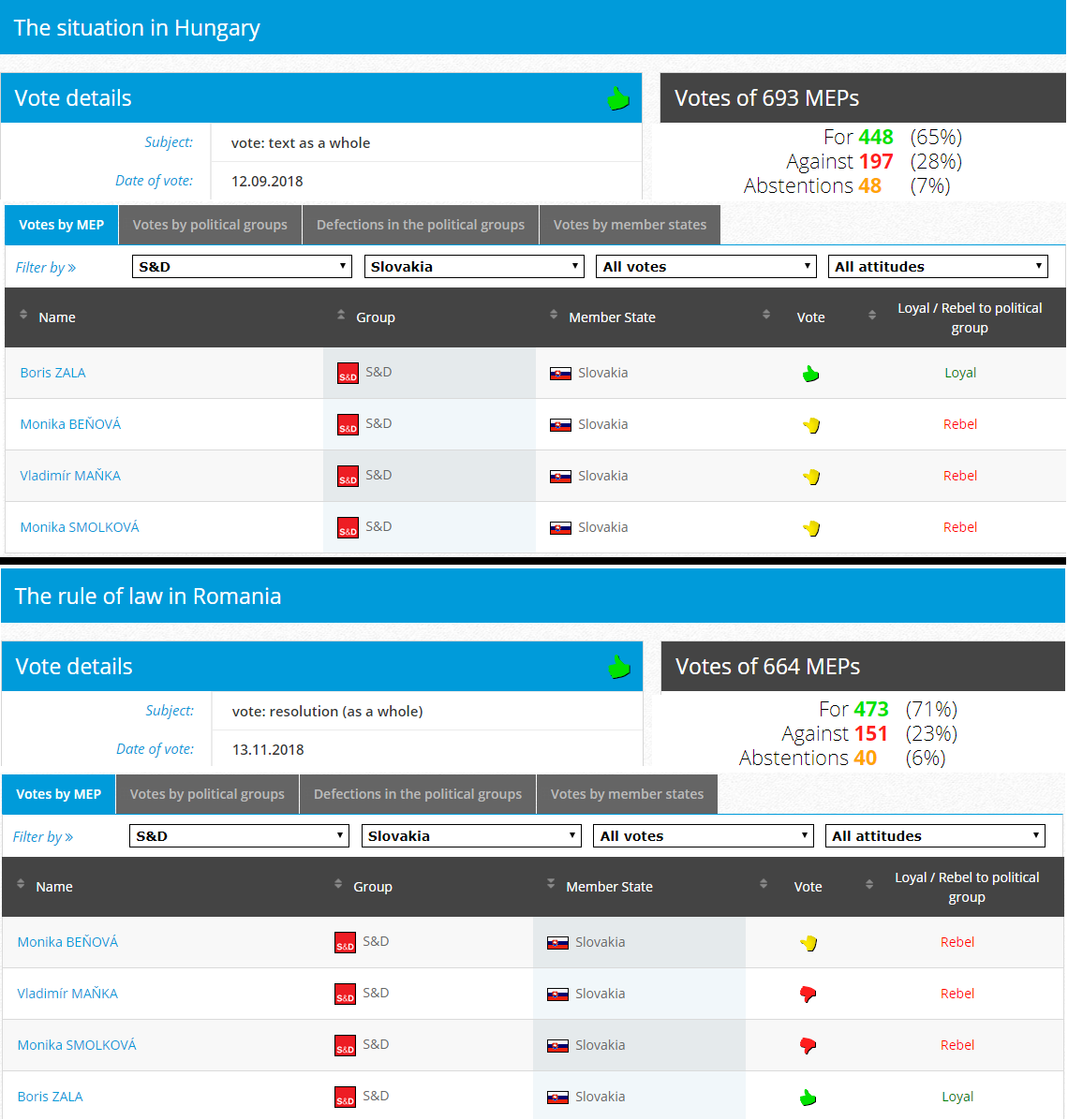

If three of the four MEPs from the SMER were identified as reliable people by George Soros’s networks, it is clear that these people – apart from Boris Zala – did not systematically follow the instructions of their group on the votes relating to the situation in Hungary or Romania.

The situation of the SMER and the PSD is similar to that of Fidesz with the EPP: despite some differences, nobody seems to be interested in a divorce that would weaken the social democratic group and marginalize the excluded.

If the situation of the SMER within the social-democratic group does not seem to give rise to any particular concern, it would be interesting to see how the situation will evolve with the elected representatives of the Romanian PSD while a first vote of the European Parliament took place against the Romanian government and that Romania has just taken the rotating presidency of the European Union.

Coordination beyond political groups?

It is therefore very unlikely that the coordination of the various oppositions to the European Union’s orientation could melt down into a single parliamentary group during the 2019-2024 parliamentary term.

Moreover, it is not certain that this would be beneficial to the reformist tendencies, since a EPP and a social-democratic group purged of their troublemakers would certainly be numerically somewhat weakened but could – with the liberal group ALDE – constitute a majority central bloc and do not suffer anymore from internal disputes.

Even with a possible populism`s surge, it is still likely that with the addition of the social-democratic groups, ALDE and EPP have a comfortable majority in the European Parliament, even if we were to cut parties like Fidesz or the PSD.

Unless hard-to-control political phenomena such as the Five Star Movement in Italy or the movement of Yellow Vests in France (which it is impossible to predict if it will have an electoral incarnation, and if yes, which one) emerge elsewhere in Europe and contribute to the weakening of traditional majorities.

Unless the current balances are upset, the path of reform may occasionally take shape through coordinations that go beyond the cleavage of political groups or even national political traditions. In this regard, the rejection of the report against the Romanian government by Fidesz MEPs (while the PSD MEPs had mainly voted on the Sargentini report two months earlier) constitutes a model of political pragmatism. It should be noted, however, that many supporters of the line of PSD leader Dragnea criticized the PSD deputies’ vote against Hungary, and that it is conceivable (as in Czechia) that the new PSD Euro-parliamentarians will be more carefully selected, in order to match with the line of their party.

It is not to be excluded that the contempt of Westerners and Brussels for the rulers of Central and Eastern Europe is the best way to bring them to strengthen their solidarity and political identity beyond the V4, all with the support of Western populists who praise their governance.