Hungary – A new campaign by the government against Soros and Juncker; rising criticism in the EPP against Fidesz; and looking ahead to the local Hungarian elections

By undertaking a new billboard campaign against well-known financier George Soros, but also the current President of the European Commission, Jean-Claude Juncker (of the European People’s Party [EPP], Christian Democrat), Viktor Orbán’s administration was not afraid to anger either Brussels or Fidesz’s own partners in the EPP – of which they are still a member – three months before the European elections, despite growing criticism.

A break between Fidesz and the EPP?

The poor relations between Orbán and Juncker are nothing new. We can remember the “friendly” slap Juncker gave Orbán during a European summit in 2015, at the height of the migration crisis. This gesture was a rare inelegance – even if occurring after an enjoyable champagne lunch – on such a high political level.

Orbán, always a wise strategist, is aware of his strengths and weaknesses. He’s used to calmly facing unpleasant situations, waiting for the right moment to counterattack later. This is how he operates on both the national and international levels.

Already in July 2018, the Hungarian Prime Minister made no secret of the fact that he is glad that the European Commission’s current term, under Mr. Juncker’s leadership, is ending: “The European elite has failed, and the European Commission is the symbol of that failure. This is the bad news. The good news is that the European Commission’s days are numbered. And I have counted them: it has some three hundred days left before its mandate expires.”

During the vote on the Sargentini report in September 2018, when the European Parliament voted to sanction Hungary for its supposed violation of the “rule of law,” the break between a large number of the EPP’s representatives and those of Fidesz was readily apparent. Among the EP’s representatives, the vote went as follows:

- 114 in favor

- 57 against (including the 12 Fidesz MEPs)

- 28 abstentions

- 20 absentees

Among the 114 MEPs who voted in favor of the Sargentini report, one can find Manfred Weber of Germany, who was chosen – with Fidesz’s support – in November 2018 to be the EPP’s candidate to succeed Juncker as President of the European Commission. After the vote, Mr. Juncker declared that he regarded Fidesz’s membership in the EPP as a problem.

Other leading figures of the EPP, who were previously favorable towards Fidesz, might now turn against it. For example, Joseph Daul, the EPP’s President, was once a defender of Orbán’s; but recently, for the first time, Daul publicly criticized him and the anti-Juncker billboard campaign in a tweet:

Other EPP representatives likewise distanced themselves from the new Hungarian campaign. Unsurprisingly, Austria’s Chancellor, Sebastian Kurz, is among them. The MEPs of his party, the Austrian People’s Party (ÖVP), voted in favor of the Sargentini report. Despite the populist rhetoric which brought him to power, the young Austrian Chancellor remains strongly linked to the Soros networks. He recently welcomed Mr. Soros to Vienna to discuss the move of Soros’ university, Central European University, from Budapest to Vienna following pressure from Fidesz. Kurz also didn’t hesitate to distance himself from Johann Gudenus, the leader of the Austrian Freedom Party’s (FPÖ) parliamentary bloc, when he criticized Soros, despite the fact that the FPÖ is currently Kurz’s coalition partner.

Another criticism came from Juncker’s possible successor, Manfred Weber. Weber declared that with only 13 MEPs out of 751, Fidesz won’t be able to decide Europe’s future. If this merciless call back to reality seems very true, let’s mention that Fidesz doesn’t have 13 MEPS, but only 12; and also the fact that the next European Parliament will have only 705 MEPs instead of 750, due to Brexit.

Moreover, the likely weakening of the majority groups in the European Parliament (the EPP and the Socialists) in the May 2019 elections will strengthen Fidesz within the EPP. According to the polls, Fidesz might win more MEPs in the EPP (if they in fact remain in the EPP) than the French Republicans. Given the comparative demographic weight of France and Hungary (the number of MEPs each country has depends on the size of its population), this says a great deal about Fidesz’s political strength in a Europe where a lot of the Member States are facing political instability.

With its likely weakening, can the EPP get rid of Fidesz and its partners? The Visegrád Post already raised this question in a study about the possible new combinations of European parliamentary blocs following this year’s elections. At the same time, seeing the anger of a growing number of EPP members over Fidesz’s membership in their group, can this situation continue?

One thing seems clear: Fidesz won’t leave the EPP, which would only become a martyr if the bloc decided to exclude them. Thus, the coming weeks will be rife with tension within the EPP.

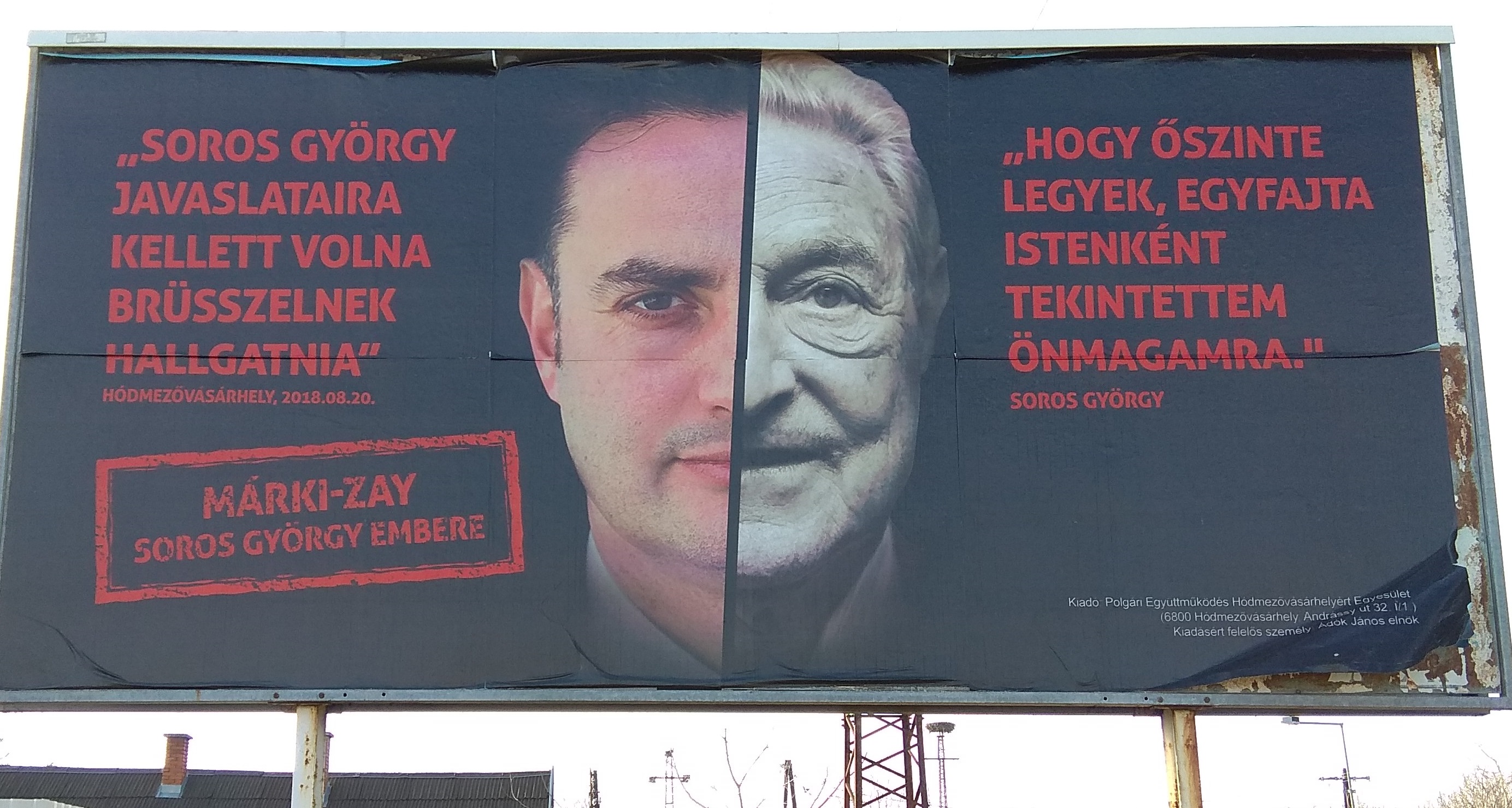

The other target of Fidesz’s billboard campaign: Péter Márki-Zay, as a prelude to the upcoming local elections

Soros and Juncker are not the only targets of this billboard campaign. Other Fidesz billboards appeared simultaneously, targeting the Mayor of Hódmezővásárhely, a town of 45,000 citizens in southern Hungary.

Why is this? There is no question that Fidesz will lead in the European elections in Hungary. But the issue at stake is not only for Fidesz to gain as many MEPs as possible in order to influence European politics, but also to influence the balance of power domestically prior to Hungary’s local elections in October 2019. In order to retain its rule over the majority of Hungary’s cities, towns, and counties, Fidesz has a vested interest in striking a blow in the European elections as well.

The turnout in the European elections is usually low, so the primary task of the political parties is to mobilize their core voters better than the other parties can do. This might allow Fidesz to obtain an even better result than it did during the Hungarian national election in April 2018, when they received 49% of the votes.

The local elections will also be a fresh opportunity for the opposition parties to achieve what they were unable to accomplish during last year’s national election: coordinating all the Left-liberal parties (the MSZP, DK, and Párbeszéd) with Jobbik (formerly of the radical-Right but nowadays a pro-EU and center-Right party, which is still the primary opposition). This strategy was launched in February 2018 during a local mayoral by-election in Hódmezővásárhely, which led to the victory of Péter Márki-Zay – an independent candidate who was supported by all the opposition parties – against the Fidesz candidate.

Márki-Zay, who became the figurehead of an “alternative” conservatism in opposition to Orbán’s rhetoric, has called for a technocratic government in order to deconstruct Orbán’s legacy and realign Hungary with the EU’s line. He has advocated for a withdrawal strategy between the opposition parties in the individual electoral districts in order to defeat the Fidesz candidates, in which the other parties would withdraw their candidates in order to give the one with the best possibility of unseating Fidesz the greatest opportunity to do so by concentrating the opposition’s energies. But in April 2018, this strategy wasn’t followed by the opposition parties. In the next round of local elections, however, they might be ready to work together more closely in accordance with the “Hódmezővásárhely model” in a large number of towns and cities.

Jobbik’s Vice President, Márton Gyöngyösi, declared in an interview that creating a common list for all the Hungarian opposition parties in the European elections was not being considered given that the European Parliament’s electoral system is a proportional system based on lists. But he added that the coordination of all the opposition candidates in the local elections does indeed make sense.

Such coordination between all the opposition parties has grown significantly since April 2018, as for example during the demonstrations against the so-called “slavery law,” which allows companies to raise the number of overtime working hours for employees in some fields. This has led to an offensive against the Left-liberal parties in the pro-Fidesz conservative media for their new common cooperation with Jobbik, leading them to highlight some of Jobbik’s more controversial statements from previous years.

The municipal election with the highest stakes will certainly be Budapest’s, where Fidesz is less popular. After twenty years of liberal domination under Gábor Demszky of the Alliance of Free Democrats (SZDSZ), Fidesz finally succeeded in taking the city from them in 2010 with István Tarlós, who will again be Fidesz’s candidate in October, seeking a third term.

While part of the Left wing began the campaign during their primary elections, the Green Party (LMP) and Jobbik might agree to support the independent candidate, Róbert Puzsér, a polemicist and controversial journalist, and one may expect other withdrawals by candidates in favor of Puzsér, who they feel has the best chance against the Fidesz candidate. Puzsér declared in an interview that, with the exception of István Tarlós and himself, there was no other candidate who would have a chance to win Budapest’s municipal election. This was a way to attempt to discredit Gergely Karácsony’s candidacy, who wants to mobilize the liberal-Left to support him instead.

Orbán, the forward

One thing is certain: the European and local elections will make for another dramatic year in Hungarian political life.

Orbán, the football fan, remains a forward, and it’s likely he will keep going forward at both the national and European levels. This forward strategy has been a success at the national level. This has been a surprise for most Western Europeans, who are used to seeing polished and softer campaigns.

This offensive and tactless strategy is being carried out in order to obtain the best possible results as soon as possible, without taking into consideration some of the consequences, which might anyway become less important given some of the EU’s serious problems on the horizon: a difficult Brexit, an economic crisis which is being planned by the directors of the central banks, and an ongoing migration crisis. Moreover, by choosing the tone and the topic for the debates, Orbán keeps setting the field for the game, and is always a step ahead of his opponents.

Who knows where this strategy will lead, which has allowed the Prime Minister of a modestly-sized country of less than ten million citizens to become a major player in European – and even global – politics? Hungarian citizens will certainly be giving their part of the answer in the upcoming elections.