Hungary – With eight months to go until Hungary’s spring 2022 parliamentary election, the election campaign is now fully under way.

In an attempt to topple Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz, which has been in power with a two-thirds supermajority in parliament since 2010,

an unprecedented coalition of six political parties (and various other personalities or more marginal formations) is preparing to run against the prime minister’s conservative party.

This coalition, which gradually took shape in the days following the Fidesz victory in 2018, was clearly signalled during the summer of 2020 and its contours carefully worked out since then.

For their coalition to take shape, the participating parties have decided to go through a primary election, based on the American model that has now been widely exported to Europe.

The six coalition parties are:

- The DK (Demokratikus Koalíció; Democratic Coalition), a liberal and Euro-enthusiastic party led by former Prime Minister Ferenc Gyurcsány (2004–2009) and his wife Klára Dobrev, MEP. It remained stuck with low support for quite a long time (it got 5% of the vote in 2018) because of the competition of the MSZP (whose electorate it eventually managed to largely win over) and the extremely controversial personality of Ferenc Gyurcsány following the events of autumn 2006. In the European elections of May 2019, the DK finally broke through and became the leading opposition party (with 16% of the vote).

- Jobbik, a former radical nationalist party (considered in the early 2010s to be the most extremist party in Europe with elected MPs, and often accused of anti-Semitism or even neo-Nazism) which became progressively centrist from 2016. Since early 2020, it has been led by Péter Jakab.

- Momentum, the movement of young liberals led by András Fekete-Győr. After contesting its first election in 2018 (where it obtained 3% of the vote and no elected MP), the Momentum party made a breakthrough in the May 2019 European elections (with 10% of the vote and 2 MEPs).

- The MSZP, a socialist party which has been in sharp decline for the past ten years, but which still has parliamentary representation.

- The small Párbeszéd (Dialogue) party, usually recording low support in opinion polls, but co-led by Gergely Karácsony, the mayor of Budapest.

- The LMP, an environmentalist party represented in parliament since 2010, which has been on a downward trend since 2018.

These six parties are joined by various smaller formations, including in particular the MMM, led by the mayor of Hódmezővásárhely, Péter Márki-Zay, who in early 2018 pioneered the coalition of all opposition parties (Jobbik included).

The primary, for which citizens’ signatures have been collected since 23 August, will take place in September (with a single round of voting for the 106 single-member constituencies and the first round of voting for a candidate for prime minister) and in October (with the second round of voting for a candidate for prime minister).

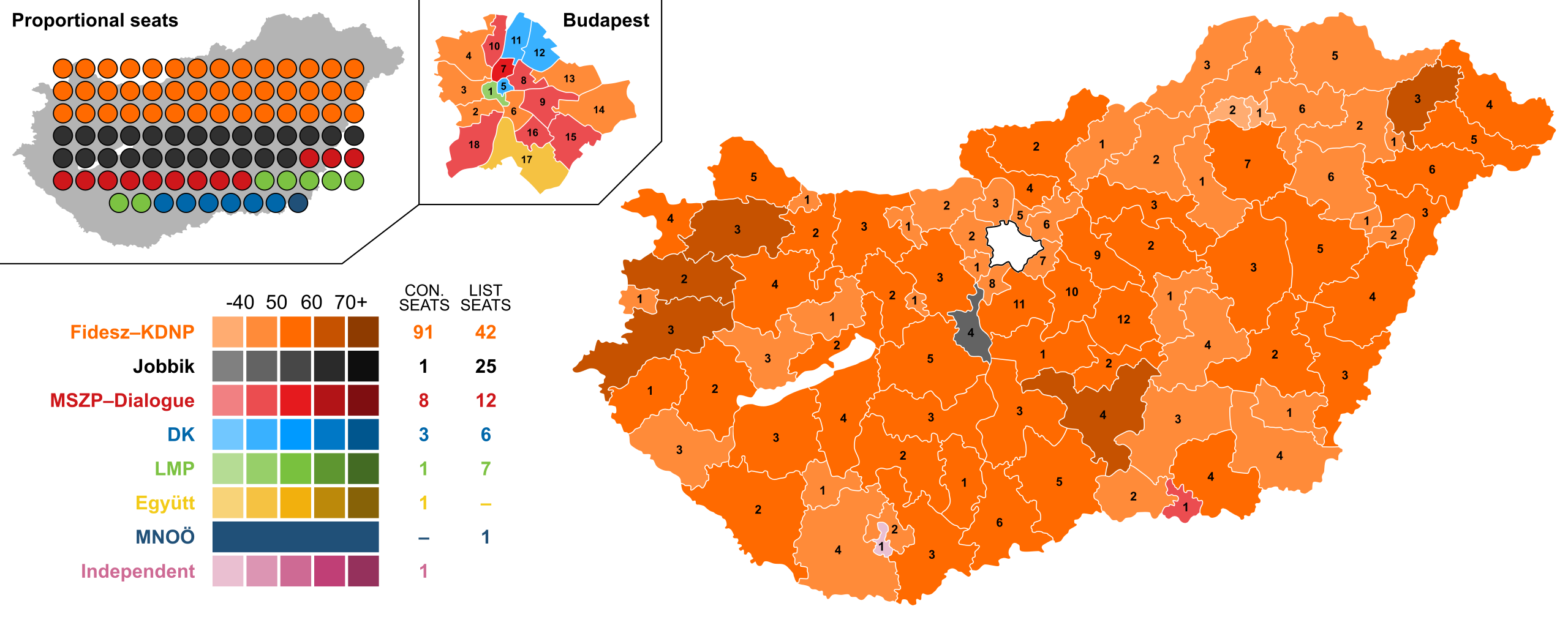

The main objective is to present single candidates in the 106 single-member (one-round) constituencies, so as not to repeat the situation of 2018, when vote-splitting between opposition candidates favoured Fidesz, in particular for MPs elected in constituencies with a first-past-the-post ballot.

The six parties organizing the primary, as well as additional groups and other opposition MPs currently without a party, have thus been able to present or support different candidates in each constituency, and every Hungarian citizen who will be 18 years old in April 2022 can take part in the vote to decide between them.

Seven potential candidates for prime minister

There will finally be seven contenders in the race to become the coalition’s candidate for prime minister: Budapest mayor Gergely Karácsony (with the support of his Párbeszéd party, the MSZP and the LMP), Jobbik leader Péter Jakab, Klára Dobrev (DK), Momentum leader András Fekete-Győr, Hódmezővásárhely mayor Péter Márki-Zay, József Pálinkás, and a last-minute candidate in the person of Áron Ecsenyi, a libertarian opposed to public health restrictions against the Covid pandemic.

Barring any surprises from Fekete-Győr or Márki-Zay, the three favourites to make it to the second round (planned as a run-off between the three top contenders) are Gergely Karácsony, Klára Dobrev and Péter Jakab. While it is difficult to say who will win the primary, due to the strengths and weaknesses of the different competing personalities, the mayor of Budapest Gergely Karácsony is probably the one who has the best chances of winning against Fidesz in 2022.

Indeed, for historical reasons, Péter Jakab (who has to take responsibility for his party’s past) and Klára Dobrev (who has to contend with her husband’s past) both have notable weaknesses, likely to make it difficult for them to garner support from large parts of the electorate.

The pro-government press is focusing its attacks on Gergely Karácsony, referring to both his poor level of English and his management of Hungary’s capital (with a significant increase in traffic problems, delays in the renovation of the Chain Bridge, etc.), and accuses him (as well as the other candidates) of being Ferenc Gyurcsány’s puppet.

What about the programme?

As for the programme of this unprecedented coalition, you would search in vain for a detailed manifesto. Apart from the unrestrained criticism of Fidesz’s responsibility for everything that goes wrong (or not well enough) in the country, the driving idea is quite simple: to put an end to “corruption”, and to integrate further into the European Union, in particular by joining the eurozone and the European Public Prosecutor’s Office.

On the Fidesz side, in a national and international context (the economic crisis following the measures against the Covid pandemic, Joe Biden’s victory, weakening of Fidesz’s position in the EU after leaving the EPP) that is more complicated than in 2018, the situation is quite similar in terms of a political programme, or rather the lack of one. Fidesz is orienting its campaign towards its now classic values and themes: conservative nationalism, opposition to illegal immigration, denunciation of the Soros networks, (partial) opposition to the policies of “Brussels”, and – more strongly in recent months – the denunciation of LGBT ideology.

It should also be noted that, apart from the question of “Eastern” vaccines (the Chinese Sinopharm and Russian Sputnik-V), health policies against Covid are not a subject of profound disagreement between Fidesz and the coalition opposition parties.

It is also difficult to determine the impact of the pandemic on the election. Indeed, in addition to the economic crisis and the small parties that are trying to position themselves in this niche, there is also the question of the adult population that is currently unvaccinated (about one-third of adults at the end of August 2021). This includes a large number of people from the gypsy community, which has been strongly in favour of Fidesz in recent years.

Little space left for other political voices

Apart from the two poles (Fidesz and the opposition coalition) that largely dominate Hungarian politics, only the nationalists of the Mi Hazánk party (formed from a split from Jobbik in 2018) led by László Toroczkai can reasonably hope to break the 5% barrier and take a seat in the next parliament. In addition to the classic themes of Hungarian radical nationalism, especially on the issues of “gypsy criminality”, the Mi Hazánk party has also positioned itself against Covid restrictions since January 2021.

The opposition to public health restrictions is also the niche chosen by the (monothematic) Normal Life Party (NÉP; Normális Élet Pártja) founded by pharmacist György Gődény, the first figure to make a mark in the Hungarian media on that theme since the beginning of the pandemic.

The enigmatic and satirical Hungarian Two-Tailed Dog Party (MKKP) could well capture some votes on the left, or even make a surprise breakthrough in a context of deconstruction. It may be more difficult for the Polgári Válasz (Citizens’ Response) party, which includes two former Jobbik MPs, János Bencsik and Tamás Sneider, who are also trying to find their way between Fidesz and the coalition parties, while keeping their distance from the radical nationalism (from which they originate) now embodied by Mi Hazánk.

It can also be assumed that the now very marginal Communist Party (Munkáspárt), led by Gyula Thürmer, who worked alongside János Kádár and whose conservative positions can sometimes seem surprising from a Western perspective, will also put up a list of candidates.