By Olivier Bault.

Poland – Two elections won by PiS, a thriving economy, a general offensive by the LGBT lobby, and an endless conflict with Brussels.

After the partial victory of PiS and its allies in the municipal and regional elections in the autumn of 2018, the Polish opposition pinned its hopes on the year 2019 as an opportunity to seize power back from Jarosław Kaczyński’s party. The European elections in May, which were supposed to be more favourable to the left and the liberals because of expected higher abstention among “Eurosceptics” and the rural electorate, were supposed to serve as a springboard before the October national elections. Unluckily for the opposition, PiS obtained a much better result than the “European Coalition”, which included liberals, the post-communist left and the PSL agrarian party (which governed Poland within the coalition led by the liberals of the Civic Platform, PO, from 2007 to 2015). One reason for the opposition’s May defeat was probably its leftward shift on societal issues, initiated by the Mayor of Warsaw (from PO) with the signing of his highly controversial “LGBT+ Declaration” in February, which was seen as the starting point of last year’s offensive by the LGBT lobby in Poland. At the same time, the Catholic Church was under increased attack, with left-wing media bringing up old cases of paedophilia, some of them real, as in the documentary film “Tell No One”, and others made up. This second offensive in fact started in the autumn of 2018 with the release of the violently anticlerical fiction film “Clergy”,which benefited from unprecedented media coverage.

After its defeat in the European elections, the “European Coalition” split into three blocks: the liberals maintained their progressive-liberal orientation within the Civic Coalition led by PO (which governed with the PSL from 2007 to 2015), the left moved even further to the left (both in the societal, progressive sense and in the socio-economic sense) and the PSL returned to its more conservative, Christian values.

However, this did not prevent the “United Right” coalition led by PiS from convincingly winning the Parliamentary elections held on October 13. It must be said that the conservative right benefited from several factors. One was still the perceived radicalisation of the liberals, who were very much engaged in supporting LGBT “Equality Marches”, which were more numerous than ever in Poland in 2019, and which were also particularly aggressive towards Catholics. That in turn enabled PiS to position itself as the champion of Polish identity, of the family and of Christian values. Speaking of the ideological offensive under way in Poland, the Archbishop of Krakow drew the attention of international media in August when he mentioned in a sermon the “rainbow plague” which has replaced the “red plague” in the country of John Paul II. And the year ended with a resolution of the European Parliament criticising Poland for its resistance to the LGBT ideology attacked by archbishop Jędraszewski, which by contrast is very much in vogue in Brussels.

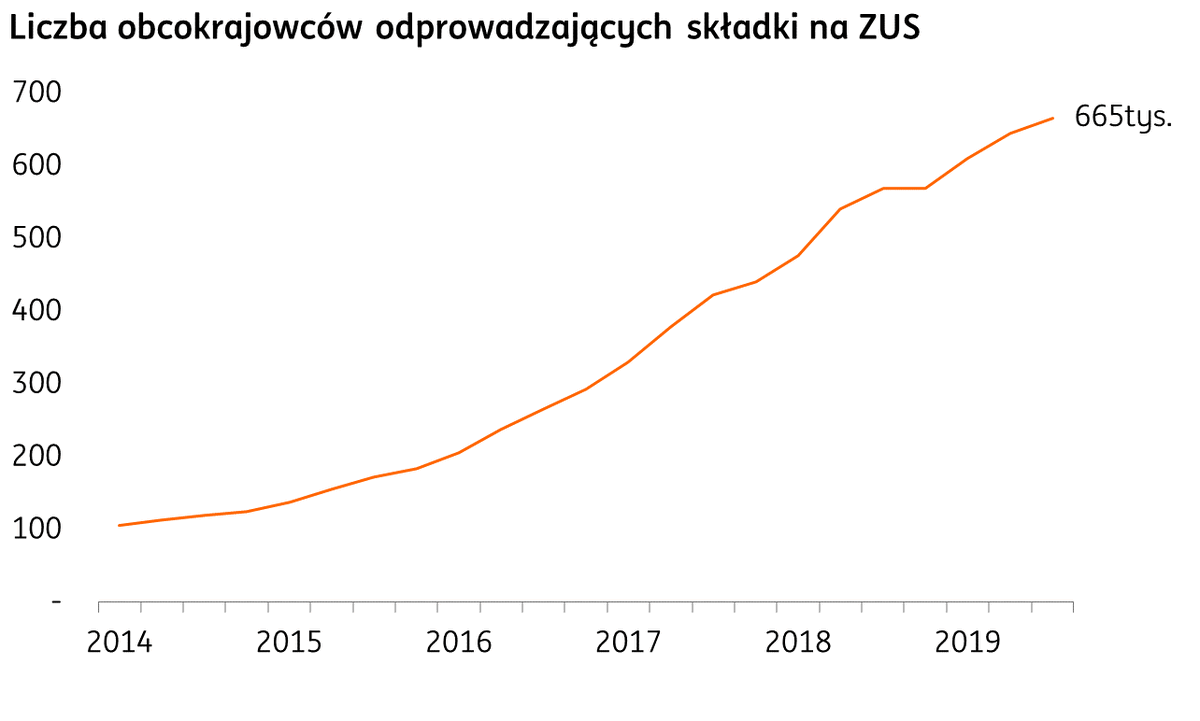

Another factor working in favour of PiS has been a thriving economy and a narrowing budget deficit, in spite of the generous (by Polish standards) social policies put into effect by Kaczyński’s party. The very positive picture of the economy was marred only by a year-to-year inflation rate that reached 3.4% in December, the highest level since 2012, but this became known only at the beginning of 2020. With unemployment at its lowest since the transition to the market economy in 1989–90, standing at 3.1% of the active population in the third quarter of 2019 as per Eurostat criteria, and 5% in October 2019 according to the Polish calculation method (used by the Central Statistical Office), work-related immigration remained on an upward trend last year, with more than 665,000 foreign workers contributing to the Polish social security system (ZUS) at the end of the third quarter versus 569,000 a year earlier. Those foreigners are predominantly Ukrainians (almost 500,000 social security contributors at the end of the third quarter of 2019). Obviously, such statistics include only foreigners employed legally in Poland; the total number of Ukrainians in the country is estimated at somewhere between 1 and 2 million.

Because of this, Poland remained the EU country that issued by far the most first residence permits. Eurostat data published in 2019, covering 2018, showed that as in 2017, Poland is the EU’s leading country in terms of first issuances of residence permits on all grounds, and it accounted for well over half of first work-related residence permits in the EU. In total, 635,000 first residence permits were issued by Poland in 2018, against 544,000 by Germany, 451,000 by the UK, 265,000 by France, 260,000 by Spain and 239,000 by Italy.

At the same time, the figures published in 2019 showed that the number of Poles living abroad declined slightly in 2018 for the first time in 30 years, thanks to Brexit and to the good economic conditions in Poland. However, there were still 2.45 million Polish emigrants in 2018, including 2.15 million in Europe (compared with 38 million living in Poland).

Meanwhile, the year 2019 saw the conflicts between Brussels and Warsaw initiated under the Juncker Commission move to the Court of Justice of the EU. However, the new European Parliament and the Von der Leyen Commission seem to be taking a similar line as their predecessors in this matter. We should therefore expect a rather agitated year 2020, with the prospect of a presidential election in which the current president Andrzej Duda starts as favourite, but also with the likely worsening of relations with Brussels, which is being exacerbated by the Polish opposition itself. Significantly, in 2019, for the first time since Poland’s accession to the EU in 2004, a study for the European Commission showed that almost half of Poles think that their country “could better face the future outside the EU”. It must be said, however, that the results of that study are not in line with other opinion polls, showing that Poles are largely in favour of remaining in the EU in spite of intrusive interference by EU institutions dominated by the liberal left. But for how long?